CURATING THE PASSAGE OF LOVE

Pamuk tells the story of a love so obsessive that its progress must be catalogued and displayed in a shrine of its own.

“But after our first three outings I came to notice that such ecstasy was inevitably followed by the familiar despair, and so, as I sat across from her, thinking how soon I would miss her, foreseeing the pain of the days to come, I would discreetly pilfer various objects from the table as reminders of the happiness I’d felt there and then—and to fortify myself later when I was alone.”

One thing invariably leads to another and I feel fortunate that on Diwali evening last week, our friends, who had just returned from a trip to Turkey, joined us for a simple meal at short notice. Listening to stories from their recent travels made me wonder about the literature from this nation. Our conversation veered into the Turkish national drink, of course, which one of them seemed to have relished. I didn’t know then that just a few days later, I would be privy to a protagonist of a Turkish novel drowning himself in raki. Made of twice-distilled grapes and aniseed, raki, according to Wikipedia, is “the go-to spirit for celebrating a promotion or a birthday or for muting the pain of a job loss or the end of a relationship.”

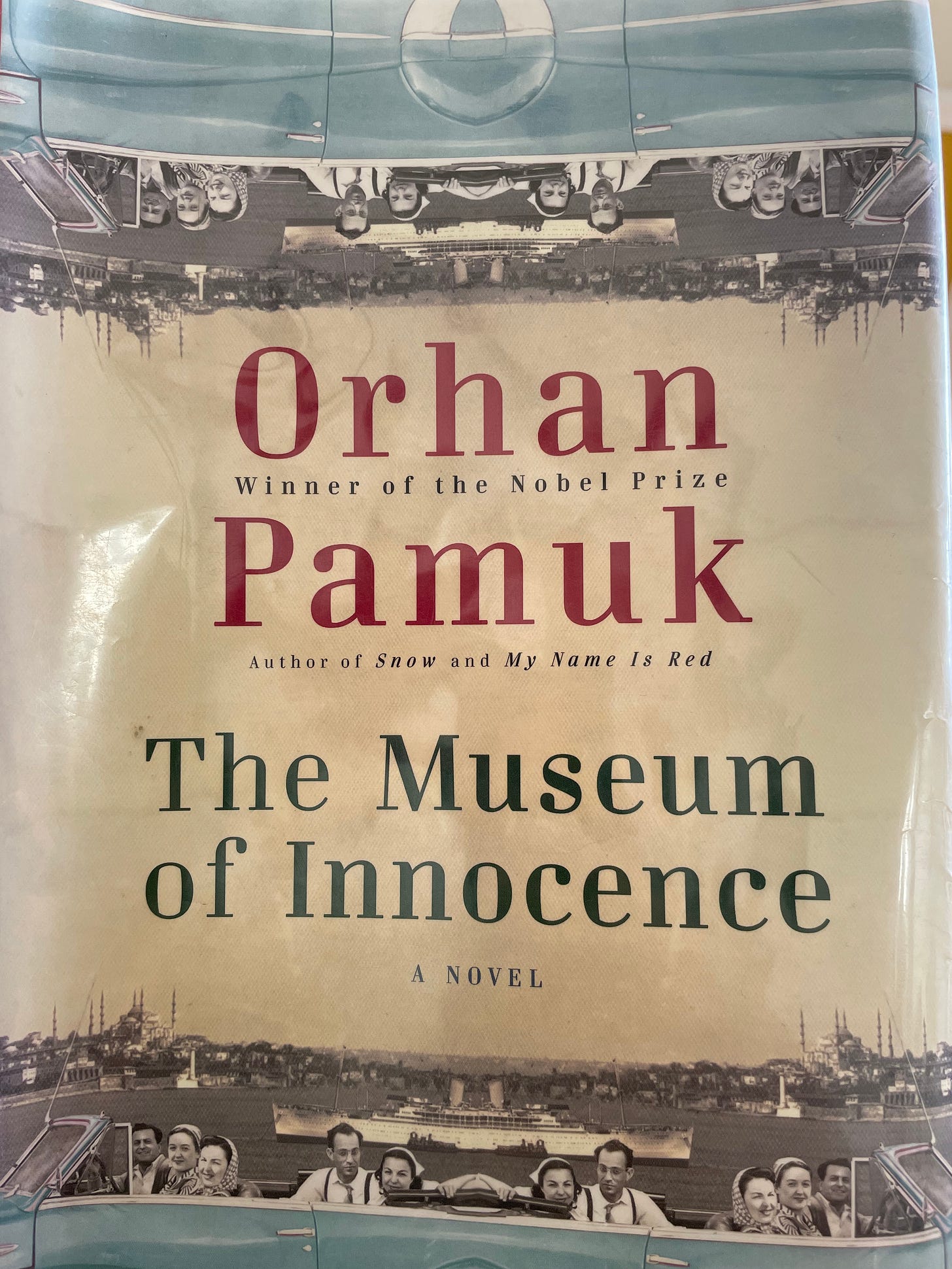

The twists and turns of a relationship, meticulously presented by one of Turkey’s contemporary greats, made this week’s pick both gripping and sad. Translated into 64 languages, Nobel laureate Orhan Pamuk—who speaks excellent English and is closely involved in his English translations—writes in Turkish. His fiction, it has been said, often artfully narrates the story of Turkey’s evolution following its creation at the end of the Ottoman empire and the country’s political, social and cultural turmoil as it emerged into modernity. I’ve known about Orhan Pamuk for decades. Yet I never wondered why he was read with the sort of reverence that is rarely handed to a writer who does not write in English.

In the translation of the Pamuk oeuvre I picked—The Museum Of Innocence translated by Maureen Freely—I can see the workings of a ruthless mind that embraces analysis. Pamuk is not just a virtuoso at weaving a sense of place into his fiction. He’s a coroner-pathologist of the human heart. He’s the ultimate curator of angst.

Great writers will themselves to do an archeological dig of sorts, by going into—the ruins of—their minds and sorting things out, by turning things around and actually picking them apart. Most of us would rather refrain from doing this. It’s much too painful. We’d rather live our lives on the surface and frolic about where life seems bearable, where we may not be reminded of our past, our faults, our missteps and our failures.

This is a story about an obsessive love. The wealthy Kemal falls hopelessly in love with Füsun (a distant poor cousin) one month before he is set to be engaged to Sibel (“the most eligible woman in all of Istanbul”). He flails about in the throes of love for Füsun, unable to think of anything or anyone but Füsun.

Through the early phase of his love, however, he displays the alacrity of a beached whale. When his fiancée-to-be asks him if something is wrong, he does not admit to the truth. He lies again and again. He has met the love of his life. He hasn’t yet slid the ring on his fiancee’s finger. What more can there be? This is the perfect time: to fess up before the mess-up. Yet he will not confess that he has made love to Füsun only some 74 times or that he would rather marry her instead. He wants the reassurance of a marriage to a woman who fits his lifestyle while having the option of an alternate life with a woman whom he finds to be his soulmate. Kemal’s inertia, his dissembling, and his disingenuousness made me nauseous. Yet, I couldn’t bear to see his twisted self on the page.

Therein lies the brilliance of Pamuk’s bloated but riveting novel that’s a paean to true love. Our protagonist is so much in love it’s not clear if he’s even sane. On most nights he has had one too many rakis. Kemal is also a collector of all things Fusun: the ruler she put in her mouth while studying math, the hairpin she used, the lipstick that touched her lips, the pencil she bit into, the half-eaten cone of an ice-cream she ate. All these become pilfered objects that are artifacts to a love that’s unending and maddening—to both him and to the reader.

Of course, the city of Istanbul becomes a character in this desperate love story and is, really, a sort of permanent exhibit to the love affair. Every little alley changes color depending on the state of Kemal’s mind and the degree of inebriation. What makes The Museum of Innocence so rich and so painful is the iridescent interplay of thought, mood, place and feeling where person and place simply cannot be pried apart.

Of all the characters in The Museum of Innocence, however, I was moved most by Sibel. She is attuned to Kemal’s every feeling. When she senses Kemal’s extreme lovesickness, his mental and physical health becomes her project. This fiancée, this woman who is torn inside, and tells him he will heal if they can go and live in a yalı, a family mansion built overlooking the Bosphorus strait. For months, they live together in this yalı while never once sleeping together. Sibel is willing to risk her reputation in society simply to get her man back until one day she realizes that it’s a lost cause. She sees it all too clearly, that the reason Kemal gets engaged to her is because he is a class conscious coward who cannot find it in himself to marry beneath his station in life.

“It’s because she was a poor, ambitious girl that you were able to start something with her so easily. If she hadn’t been a shopgirl, maybe you could have married her without causing yourself embarrassment. So that’s what made you ill, in the end. You couldn’t marry her. You couldn’t find the courage.”

Just before she leaves him never to return, Sibel makes it clear that virginity is overrated and that no one should feel obliged to stay in a relationship because of having lost or “received” one’s virginity. In a city as stuffy and hypocritical as 1970s Istanbul, other people’s perception of a woman’s virginity trumps everything else. Although Kemal starts out as a rich playboy who wanted to have the cake and eat it too, just like many entitled males in the affluent westernized Turkish society, by the time the story ends, he experiences life on the other side amid the consolations of middle-class life.

In the end, The Museum of Innocence is an exploration of what love is and its accompanying heartache. What I found compelling as I dug deeper into this 531-page work is the point of view of a man who is desperately, hopelessly in love. He’s starstruck, he’s lovestruck, he’s jealous, he’s consumed. The lovesickness parlays into a physical debility too. Pain radiates from the pit of his stomach to his entire body. In the pragmatic and everyday world of the living, it’s called acid reflux from stress. Kemal, lies in bed and weeps, much like a spurned woman. He waits for Füsun in vain day after day. He counts the hours. He counts them in five-minute increments so that he can believe that time has not passed and that Füsun will come to be with him.

While the book is a curation of love, it’s a heavy reminder that what may be the ideal love match may not always be achievable. It’s a warning that extreme love need not pave the way to extreme happiness. Along the same lines, a modicum of love does not always lead to a colorless life. Kemal, our protagonist, has been so tainted by the brief experience of an extreme undiluted happiness that he keeps chasing it even when he knows in the corner of his heart that it will remain elusive.

The Museum of Innocence made me ponder my own (arranged) marriage. A question from a colleague from the year 1989 flooded back into my mind about the state of my marriage: “Are you guys in love? Or are you simply tolerating each other?” After laughing out loud at what was a bold and funny question, I told my colleague that I could turn around and ask that same question of just about anyone in any marriage in any part of the world.

My husband and I do not feel the same level of excitement that we felt forty years ago when we met in December 1983. Yet, despite the puerile bickering in our daily lives, we both continue to feel we are right for each other. When I see him at the airport after he has been away for many days, I have felt my heart skip a beat. This does not mean that my eyes do not roll heavenward when he starts to mansplain and tell me how to drive as I head south on highway 101. We both feel an abiding love for each other, although on some days we may hate something that each of us may have said or done.

Every pairing and every marriage is a kind of “settling”, after all, whether the couple was introduced by parents, or happened to meet on Coffee Meets Bagel. It’s a pact between two people in which they agree that the said arrangement could be mutually productive and that they may really not need to look beyond their partnership in which they have promised “to have and to hold from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, until death do us part.”

Such a powerful and beautifully articulated review! I went on an Orhan Pamuk binge some years back and emerged in a trance. It can be hit or miss with him, though.

Looking forward to whatever you have in store for us next!

"Great writers will themselves to do an archeological dig of sorts, by going into—the ruins of—their minds and sorting things out, by turning things around and actually picking them apart." So beautifully said, Kalpana. I do like Pamuk, but selectively. I think I'm happy to leave this one to you. Thanks for your always-sensitive reviewing!