BREAKING UP THE PACE

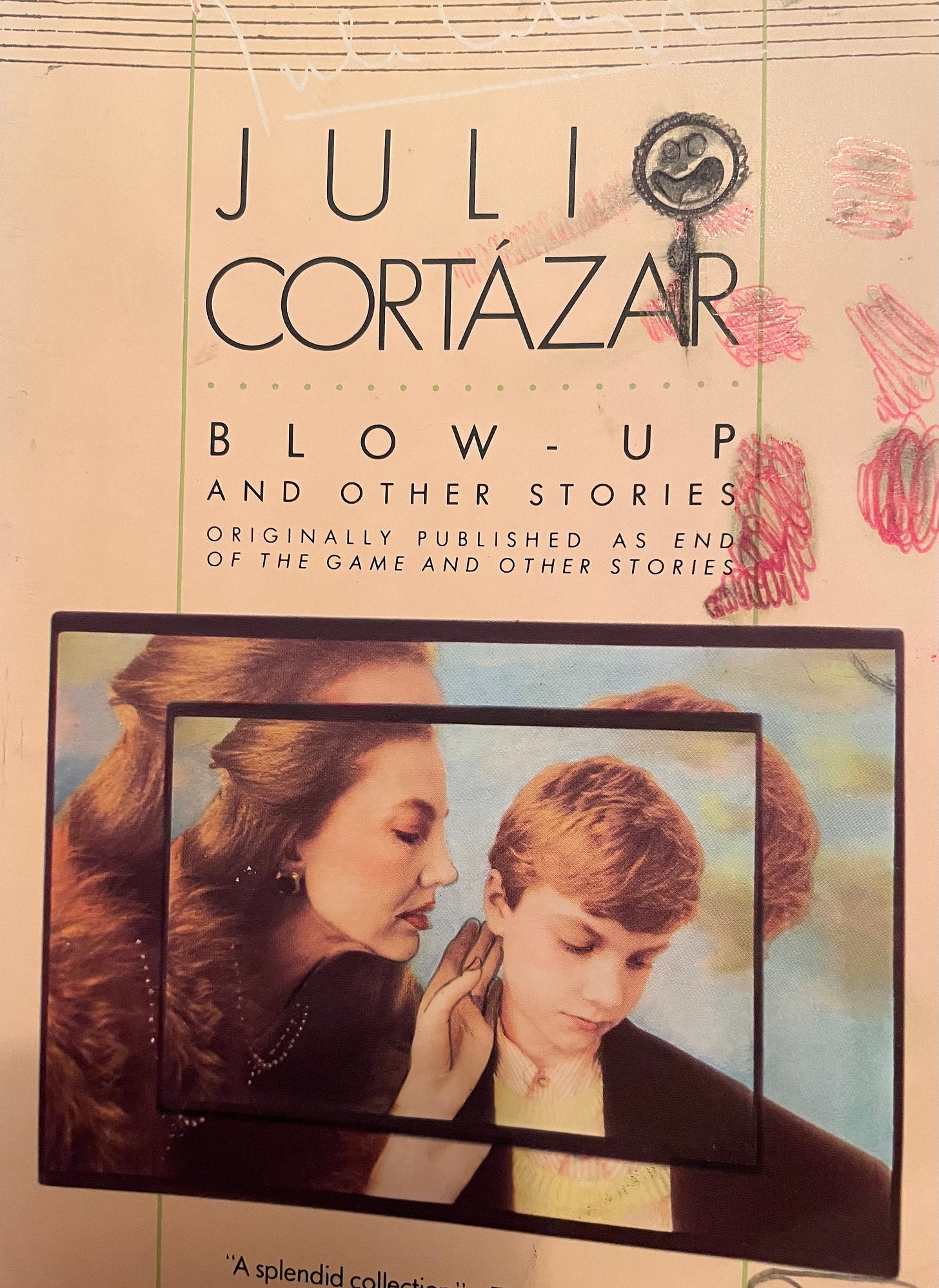

I begin this new phase of my weekly posts with a story by Julio Cortázar titled "Blow-Up" which inspired a film cowritten and directed by Michelangelo Antonioni in 1966.

On February 13, 2022, I started these posts about books in translation and I’ve found them infinitely rewarding personally. We’re well into 2025 now, over a month in, and it’s almost three years since I first began reading and writing weekly about books from around the world. This has now become a habit and, honestly, a bit of an obsession, too.

The tsundoku list in my home library of just books in translation will easily see me through another whole year of reading and writing. However, I’m now having to slow down my pace for a time while I make headway on my book project. Reading closely requires a daily commitment; writing about the reading experience demands an investment of time as well as focus that I cannot afford right now. The only option I see going forward—for a few months at least—is to read an essay or a short story in translation every week.

I thought I’d begin this new phase of LETTERS FROM EVERYWHERE with my response to a short story by Julio Cortázar who was an Argentine and naturalized French novelist, short story writer, poet, essayist, and translator.

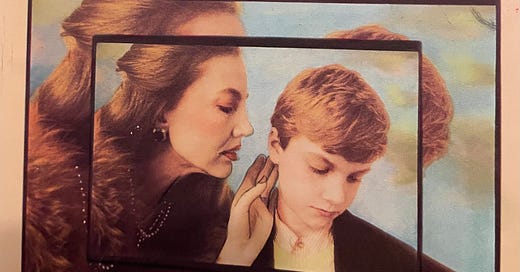

The title story of this story collection is Blow-up in which Roberto Michel, the protagonist, is a French-Chilean translator and, in his spare time, an amateur photographer, Not too much happens in this story but we watch this photographer as he goes about doing what he loves in the city of Paris.

But the sun was out also, riding the wind and friend of the cats, so there was nothing that would keep me from taking a walk along the docks of the Seine and taking photos of the conservatoire and Sainte-Chapelle. It was hardly ten o’clock, and I figured that by eleven the light would be good, the best you can get in the fall;

Michel is walking down Quai de Bourbon on the Seine when at the end of the isle he sees a couple leaning against the parapet and realizes, just as “his match was about to touch the tobacco,” that the boy in question seemed rather young.

What I’d thought was a couple seemed much more now a boy with his mother, although at the same time I realized it was not a kid and his mother, and that it was a couple in the sense that we always allegate to couples when we see them leaning up against the parapets or embracing on the benches in the squares. As I had nothing else to do, I had more than enough time to wonder why the boy was so nervous, like a young colt or a hare, sticking his hands into his pockets, taking them out immediately, one after the other, running his fingers through his hair, changing his stance, and especially why was he afraid, well, you could guess that from every gesture, a fear suffocated by his shyness, an impulse to step backwards which he telegraphed, his body standing as if it were on the edge of flight, holding itself back in a final, pitiful decorum.

This is a strange story that switches points of view midway through a sentence and throws us off every few minutes. Yet I kept reading the work for the descriptions of the city and the images of a place I once called my home. Cortazar’s describes sublime moments that photographers long for.

I’m not talking about waylaying the lie like any old reporter, snapping the stupid silhouette of the VIP leaving number 10 Downing Street, but in all ways when one is walking about with a camera, one has almost a duty to be attentive, to not lose that abrupt and happy rebound of sun’s rays off an old stone, or the pigtails-flying run of a small girl going home with a loaf of bread or a bottle of milk.

There’s a breathtaking moment in the story when the Cortazar asks questions about truth in art and the powers of interpretation.

Strange how the scene (almost nothing: two figures there mismatched in their youth) was taking on a disquieting aura. I thought it was I imposing it, and that my photo, if I shot it, would reconstitute things in their true stupidity. I would have liked to know what he was thinking, a man in a grey hat sitting at the wheel of a car parked on the dock which led up to the footbridge, and whether he was reading the paper or asleep.

Blow-up may be interpreted in so many ways. It is, certainly, the magnifying, many times over, of an image shot by a photographer, that tells us something we did not understand while staring at the image in its basic, unexpanded form. The term may be interpreted in another fashion, too, as when we blow things out of proportion. Over sixteen pages, we are led through the many possibilities of one scene that a photographer sees through his lens from just ten feet away.

As points of view shift, we get other interpretations of the world around us. This is a convoluted short story to process, but by the end it’s clear that the beauty and significance of this narrative is in the exercise itself. I believe that every reader will have a take on what he or she experienced while reading it. I saw also the power of a narrative told in the first person, in the second, and in the third. We realize one significant aspect of photo-taking which is equally applicable to every personal experience. Blow-up expresses this in a memorable passage.

I’m such a jerk; it had never occurred to me that when we look at a photo from the front, the eyes reproduce exactly the position and the vision of the lens; it’s these things that are taken for granted and it never occurs to anyone to think about them.

Though Cortázar had lived in Paris since 1951, he visited his native Argentina regularly until he was officially exiled in the early 1970s by the Argentine junta, who had taken exception to several of his short stories. With the victory, last fall, of the democratically elected Alfonsín government, Cortázar was able to make one last visit to his home country. Alfonsín’s cultural minister chose to give him no official welcome, afraid that his political views were too far to the left, but the writer was nonetheless greeted as a returning hero. One night in Buenos Aires, coming out of a cinema after seeing the new film based on Osvaldo Soriano’s novel, No habra ni mas pena ni olvido, Cortázar and his friends ran into a student demonstration coming towards them, which instantly broke file on glimpsing the writer and crowded around him. The bookstores on the boulevards still being open, the students hurriedly bought up copies of Cortázar’s books so that he could sign them. A kiosk salesman, apologizing that he had no more of Cortázar’s books, held out a Carlos Fuentes novel for him to sign.

~~~An excerpt from The Paris Review interview of Cortázar

Cortázar's original 1959 short story (original titled "Las babas del diablo") inspired a psychological mystery movie called Blow-Up in 1969. Set within the contemporary mod subculture of the city of London, the film follows a fashion photographer who actually takes Michel’s imagination even further. The photographer in this movie believes he has unwittingly captured a murder on film. Blow-up was directed by Michelangelo Antonioni, co-written by Antonioni, Tonino Guerra and Edward Bond, and produced by Carlo Ponti.