BRAHMIN FETTERS

In the chaotic struggle to decide who should cremate a dead Brahmin who had shunned a life of Brahminhood, an austere village priest finds himself ensnared by his own mental and physical limitations.

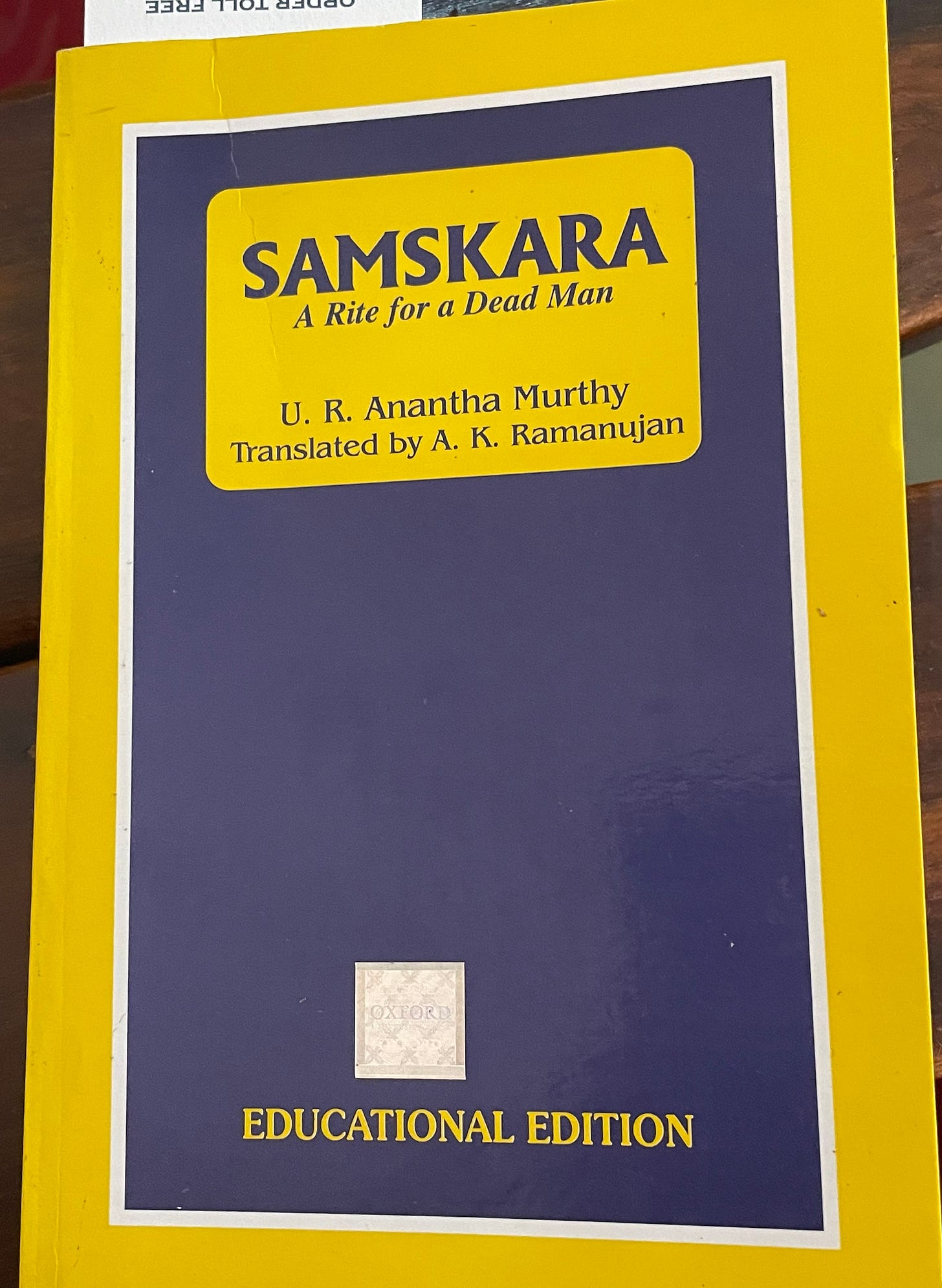

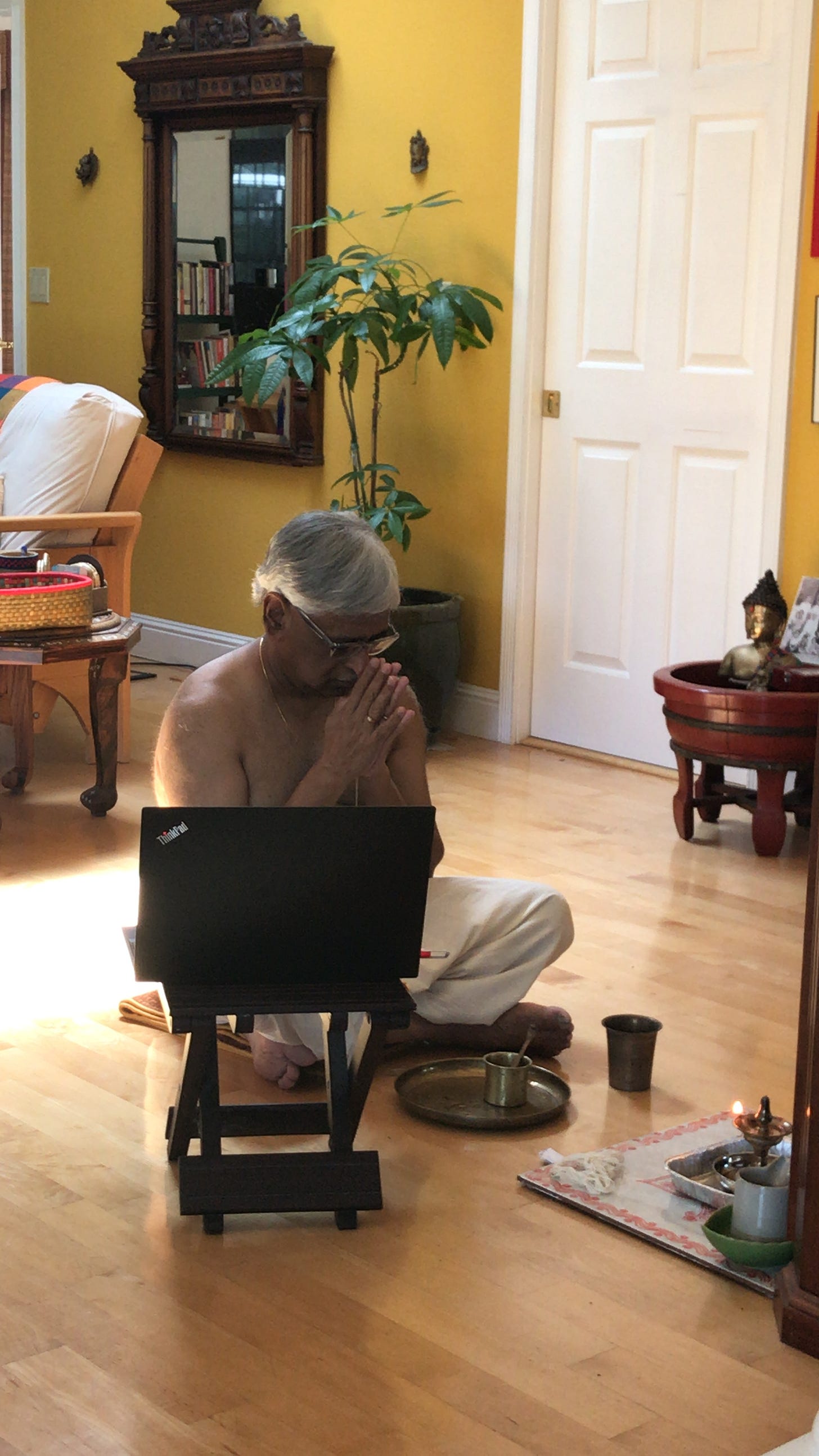

A little after I reached my husband’s home in south India on May 13th, I began reading the late U. R. Anantha Murthy’s Samskara. The timing could not have been more prescient. I’m staying in the home of my parents-in-law for about three weeks and whenever I visit their home I’m reminded of all that I inherited from my own ancestors. My husband and I are of Brahmin descent from Tamil Nadu and our ancestors hailed from the priestly classes. My paternal great-grandfather was a priest in Kerala’s Palakkad. Over the generations, the children of those in the priestly classes became civil servants, accountants, engineers, doctors and teachers under the aegis of the British empire, pontificating brilliantly in English while devoutly upholding their Brahmin mores.

Samskara, translated by the late A. K. Ramanujan, is a reminder of my early life. I cringed reading some of the passages in this novel because many ideas were a reminder of the behavior of my maternal grandfather—one of Aluva’s great landlords and philanthropists. He was one of the kindest men I’d ever known. In my place of birth, he was a legend for feeding the poor every day in the samooham across from the road. Yet this wonderful, pious man—who put a roof over the head of many distant family members who had fallen upon hard times—believed that a class of people were subhuman and that if he so much as glanced upon them, he would be polluted. He would bathe to become clean again.

Reading Samskara was a return to life with my grandparents. My past and present have been filled with echoes of characters whose beliefs are so extreme and hardened that their rigidity makes them inaccessible to others. A few days ago, I received the illustration of a family tree in which only the names of men had been jotted down. The wives were missing. So too, the daughters and the daughters-in-law. Unless immaculate conception was a forte of men in the family, I would assume that women were, in actual fact, needed to propagate many branches of the tree.

I bring it up as part of this discussion because in some orthodox Brahmin families in South India in contemporary times, women are merely objects who serve and cater to their men’s needs. This is an undercurrent that colors several aspects of Brahmin lives even today; that family chart was drawn up thus in the interests of space, purportedly, but it is yet another byproduct of a patriarchal culture that is handed down generation after generation.

Samskara is a deeply disturbing novel. I could not put it down. At the time of its publication in 1965, the book was controversial, and, likewise, the movie based on the book was banned in the year 1968 because it was perceived to be anti-Brahmin. The work spurned many societal mores, holding priesthood to the light, and questioning the rites of passage that Brahmins were beholden to throughout their lives. According to the Sanskrit dictionary, the word saṃskāra is described as a purificatory Hindu ceremony in what is a Hindu rite of passage. Saṃskāra alludes to temperament, too—as a form of “disposition, impression or behavioral inclination or a moment of recognition.”

The story is set in the orthodox society of Madhwa Brahmins in a village called Durvasapura in south India’s Karnataka. Praneshacharya has completed his Vedic education at Varanasi and has returned to Durvasapura and is considered to be the leader of the Brahmin community of his village and the surrounding ones. To ensure that he would be able to pursue a monastic existence free of wants and desires, he marries an invalid who is confined to bed; we learn that he wished to marry her even though he had many other matrimonial choices as a young man. He chooses to lead a celibate life even as a married man, thus completely rejecting the physical needs of his human self.

After their meals, the brahmins of the agrahara would come to the front of his house, one by one, and gather there to listen to his recitation of sacred legends; always new and always dear to them and to him.

The story opens with the sudden death of Naranappa, a renegade Brahmin who has consistently flouted the rules of caste and purity for years, and has been living in sin with Chandri, a woman of a low caste. He has never been excommunicated by Praneshacharya, adding to the frustration of the villagers. The question of whether he should be buried as a Brahmin divides the other Brahmins in the village. They turn to Praneshacharya, the most devout and respected guide of their community, for an answer. The fact that the news of the man’s demise arrived just before lunch time is another source of irritation in this small village.

The news of death spread like a fire to the other ten houses of the agrahara. Doors and windows were shut, with the children inside. By god’s grace, no brahmin had yet eaten. Not a human soul there felt a pang at Naranappa’s death, not even women and children. Still in everyone’s heart an obscure fear, an unclean anxiety. Alive, Naranappa was an enemy; dead, a preventer of meals; as a corpse, a problem, a nuisance.

Praneshacharya, the scholar who has an answer to everything, finds himself at his wits’ end. As Naranappa’s body putrefies, more rats die in homes across the village suggesting the bubonic plague. Vultures circle ominously above the rooftops frightening all the people. Helpless and dismayed at being unable to resolve the conflict of who must perform the cremation rites, Praneshacharya seeks an answer at the Maruti temple. The learned man pleads for a sign from the almighty and waits in vain.

What he discovers is something else entirely. Perhaps Naranappa had taught him a lesson, in life and in death. As the priest comest to terms with the limits of the human condition and spends his days in a stupor, walking away from his present, we relate to his fallibility. We feel his pain. We hear his angst. We’ve been there. We realize that the conduct of a life based on truth is much harder to achieve than one soaked in esoteric learning.

What Samskara reveals as the story progresses is also the hypocrisy of the community of Brahmins in Durvasapura; their condescension towards Naranappa for living publicly with Chandri is shocking, especially when many of them—who are so proud of their elevated Brahminical status—are openly lascivious towards well-endowed women from the “lesser” castes.

Anantha Murthy’s character delineations are an absolute delight. There are so many quotable passages. How can we forget about the miserly Lakshmana, “niggard of niggards, the emperor of penny pinchers, mother-deceiver“?

When his wife nags him about an oil-bath he gets up in the morning and walks four miles to the Konkaniman’s shop. “Hey, Kamat, have you any fresh sesame oil? Is it any good? What does it sell for? It isn’t musty, is it? Let me see.” With such patter, he cups his hands and gets a couple of spoons as sample, pretends to smell it and says: “It’s all right, still a bit impure. Tell me when you get real fresh stuff, we need a can of oil for our house.” And smears the oil all over his head.

Samskara was made into a movie in the year 1968. For anyone interested in knowing more about the filming of what became an international project, it’s absolutely worth listening to all the creative minds behind Samskara who revisit the filming experience many years later. Samskara won the National Film Award for Best Feature Film in 1970.

While the translation by A. K. Ramanujan was immensely readable, some usages made me cringe. I did wonder how the work might read in the hands of another Kannada translator by name Srinath Perur whose translations I’ve enjoyed so much: Vivek Shanbhag’s Ghachar Ghochar and Sakina’s Kiss are clearly eminently readable because of two equally terrific writers. All translations need revisiting, I’ve heard. As times change, language itself morphs and hence the constant need for newer translations of old works. In his defense, I must say that A. K. Ramanujan was a renowned poet, scholar, linguist, philologist, folklorist, translator, and playwright. Ramanujan’s academic research ranged across five languages: English, Tamil, Kannada, Telugu, and Sanskrit.

Let’s fathom this for a moment. Aside from English, this translator held forth in four of India’s regional languages known for a vast body of literature. Here I stand, a bedbug in the literary universe, unable to imbibe or share ideas in any language other than English.

So glad you reviewed this one. Samsara was serialized ( perhaps in an abridged version, I am not sure) in the Illustrated Weekly magazine in the mid 1970s. I read it when I was in first or second year of college. It is certainly a powerful work. The serialization was accompanied by some fabulous illustrations by somebody called Kavadi. I still remember those.