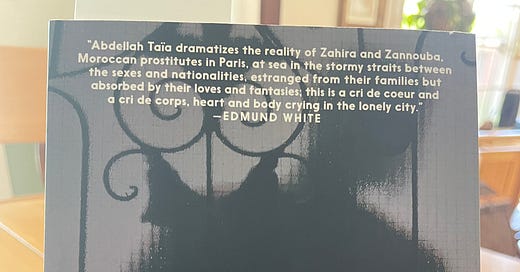

BETWEEN MOROCCO, FRANCE AND THE WORLD

In these linked stories about the uncertain lives of immigrants in Paris, we follow the heartaches of people in the diasporas in a postcolonial world.

It’s important to begin by sharing a few details about the Moroccan writer and filmmaker, Abdellah Taïa before I delve into his novella. Abdellah Taïa grew up in Morocco’s Rabat as a gay man.

Celebrated he may be today but the book’s back cover lays out his prolonged angst in a reinforcement of the words in A Country For Dying: “So many people find themselves in the same situation. It is our destiny to pay with our bodies for other people’s future.” In several interviews, Taïa describes the struggles he and his family underwent in the north-western Moroccan city of Salé, located not far from the capital, Rabat.

What affected him most, however, was to have no sense of protection from his family or society. “What destroyed me, killed me, was when I discovered that no one will help me,” he says. “The society wants to rape me, men were harassing me, some others insulting, touching, and I was the one always condemned.

“People felt they had the right to exploit me sexually. All the neigbourhood knew. Even my family knew. But they abandoned me. This was very cruel. Very tragic. I always felt and I am still feeling that way attached to my family, to the poor class, to our poor imagination, our poor situation.

I am not saying here that my family didn’t love me, in their way. I am saying that Moroccan society always sacrifices the victim, the weak, the fragile, the poorest among the poor people ... I understood one day that I would not be the victim they wanted me to be.”

~ From this Guardian story published in 2014 by Saeed Kamali Dehghan, a Guardian staff journalist who was previously an Iran correspondent

I’d started A Country For Dying several times before and I had to stop reading. Some books are so disturbing from the get-go. Hence I tend to put them back in the shelves and move on to something else. The characters described by this novella operate in a world so wretched and so distant from my own that I think I preferred to not know about it. This week, however, I picked it up and told myself I had to read A Country For Dying no matter what.

We follow the travails of three marginal characters eking out a life in the glorious city of Paris: Zahira, an aging prostitute, Zannouba, a young Algerian-born trans woman, and Mojtaba, a gay Iranian fleeing his home country to settle in Stockholm, Sweden. They’re all deeply troubled souls, and their inner torment has forced them to make choices not often acceptable to themselves or to the others who once loved them.

The price of sex is an undercurrent in this novella. This most basic of human needs, we realize, is closely linked to one’s deep longing for acceptance. To feel validated in the world we must receive an acknowledgment of our sexual identity; the inevitability of the tragedy that all too often accompanies it makes these stories powerful and hopeless.

The life of every character in this novella is determined by a need to survive. In Zahira’s case, sex is the only way her family can survive when her father dies early; she continues to support her family and her lover with her body when she goes to Paris. In Zannouba’s new life as Aziz, sex brings in money, pleasure and popularity, but we learn that it never satisfies him. He uses his manhood—and his latent womanhood—to bring pleasure to others, but when he does make a definitive choice to go under the knife to transform into a woman, he becomes ambivalent about his future.

Now that it’s happened, the obvious transformation, the more-than-necessary repair, I find myself unsatisfied again. Completely overwhelmed by the manly side that still runs through me, in my veins, that dominates my genes.

What am I going to do now?

I can’t go to the bathroom anymore. I don’t want to anymore. And to avoid needing to piss, I’ve decided to stop drinking water.

Little by little, I wither. Body. Heart. Spirit. I no longer know what to do or how to do it.

Am I a woman, completely a woman?

No.

Am I still a man?

No.

Who am I, then?

Aziz has wanted to be a woman all his life but once his physical form has changed, there’s a despair that makes his story the most heartbreaking of all. What will it take to be contented? If we could only answer that question, we may as well have struck gold.

Out of the three, it’s clear that Mojtaba will go on to lead a reasonably successful life for he knows to use people to to his end in the right way and at the right time. He is a gay man from Iran who was part of the revolution; by the time we read the letter to his mother mailed from France, we realize that his fight against the Iranian government is merely a larger fight for his sexual freedom, one that he may never win in his family, no less his nation.

Zahira, Zannouba (Aziz), Mojtaba, and the others, including Allal and Zinab are all lost by the time we close the book. It’s possible that Zinab and her lover may have found acceptance in Bombay’s Bollywood of the early 20th century. In an unexpectedly charming moment from the world of Hindi songs, Zinab sings the song below for her lover about her dilemma.

A Country For Dying is a fictional account of people but it feels so real and gritty that it’s unsettling. Clearly, there is a Paris where Arab women like Zahira fit in, for they believe they’re offering a service that helps newcomers in the city survive. This novella doesn’t give us hope. It seems that no matter how successful they are, Zahira, Zannouba (Aziz), and Mojtaba will remain misfits in society, even in one that claims to celebrate diversity but chooses to spurn people collectively when things go wrong.

Back in Morocco, too, we understand that as long as humans occupy the planet, we will be defined by our differences, not our similarities. Zahira and Allal are in love with each other but when the time comes to stand in support of each other, Zahira must make a decision. The decision she makes, however, will signify the end of her love life and, quite possibly, her life, too. When Allal discovers the source of her income, nothing matters anymore and the story turns macabre. The author gives voice to Allal in one of the penultimate chapters.

Hiding in the kitchen, you heard everything. I know it, Zahira. Your mother, heartless, condemned me. Cut off my head and feet.

You did nothing. You didn’t cry. You didn’t yell. You didn’t even try to send me a discreet signal. Nothing. The void.

Already we weren’t living in the same world anymore.

Later, I stood in front of the mirror. I looked, for a very long time. I saw what I am despite myself.

I am black. Moroccan and black. Moroccan, poor and black.

You, your and your family, were Moroccan, poor and not black.

The Paris described in this novella is a city I would never have recognized but on a beautiful morning many decades ago, I crossed my world to briefly enter another, right after I’d had breakfast in the center of town. In 1998, during my whole year in Paris, I explored every by-lane on my own and walked across the arrondissements and one day I found myself in a noiseless back alley.

In a row of a neatly stacked low-rise apartments, I found a couple of beautifully attired women standing on the roads in a certain way that made my hair stand on end. It was a setting that may have been perfectly residential. Here and there, however, some well-groomed men furtively entered the buildings, cigarette in hand. It was all perfectly above board from the looks of it. All was unusually silent, very unlike the cacophony of the stylish city a few blocks away.

Yet, almost instinctively, however, I felt I had entered an upscale red light district in this sophisticated city. A Country For Dying takes us through the city’s metro stops and suburbs and it was only natural that I’d find myself plunging into some surreal scenes in my past from the city of love.