BARA WILL QUESTION YOUR IDEALS

This Kannada short story by U. R. Ananthamurthy is a risky pick for a book club.

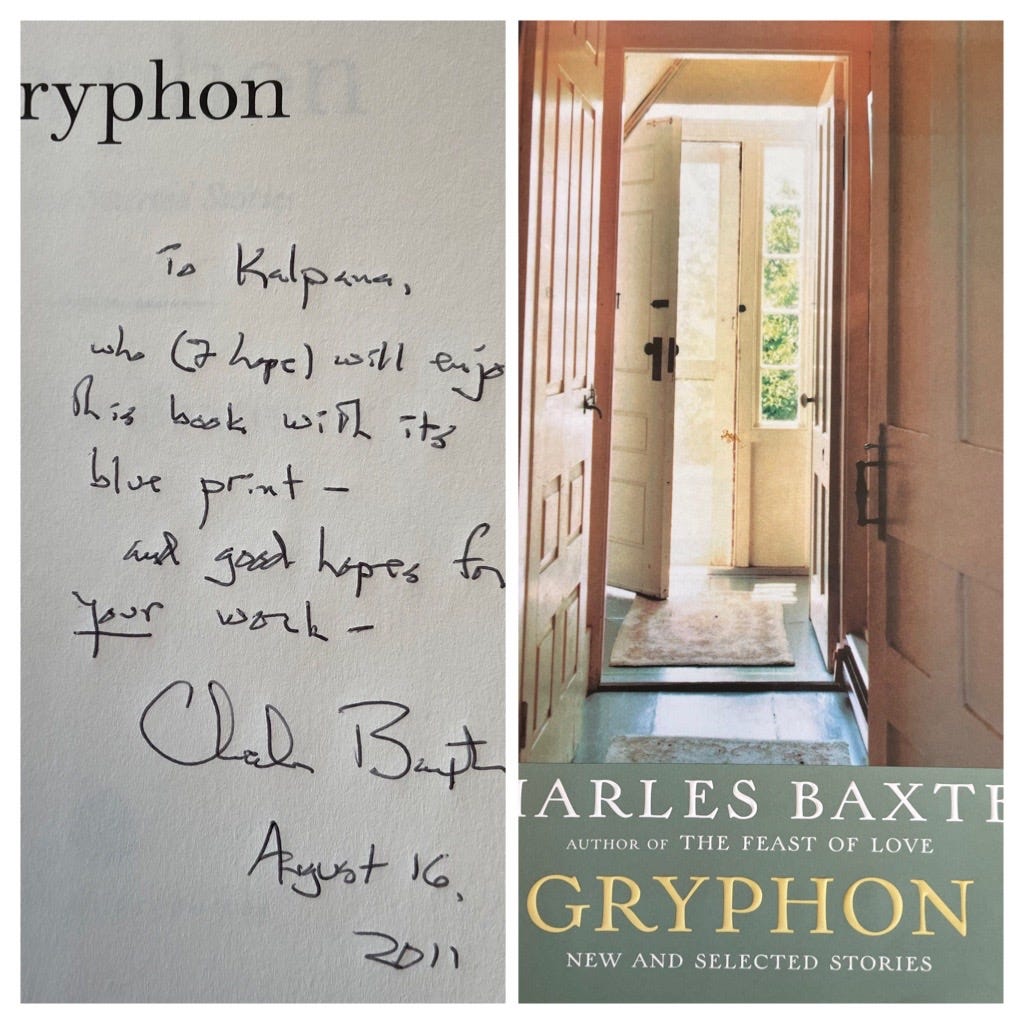

In 2011, I was at a writer’s conference in Vermont. One morning, a few of us were chatting and eating breakfast with Charles Baxter, the humble yet supremely accomplished virtuoso of the short story form. I asked him about what made a short story powerful. After enumerating what he looked for in a great story, he drilled down into the importance of an ending. “It must be inevitable”, he said, “and yet there must be a surprise, you know, a twist.”

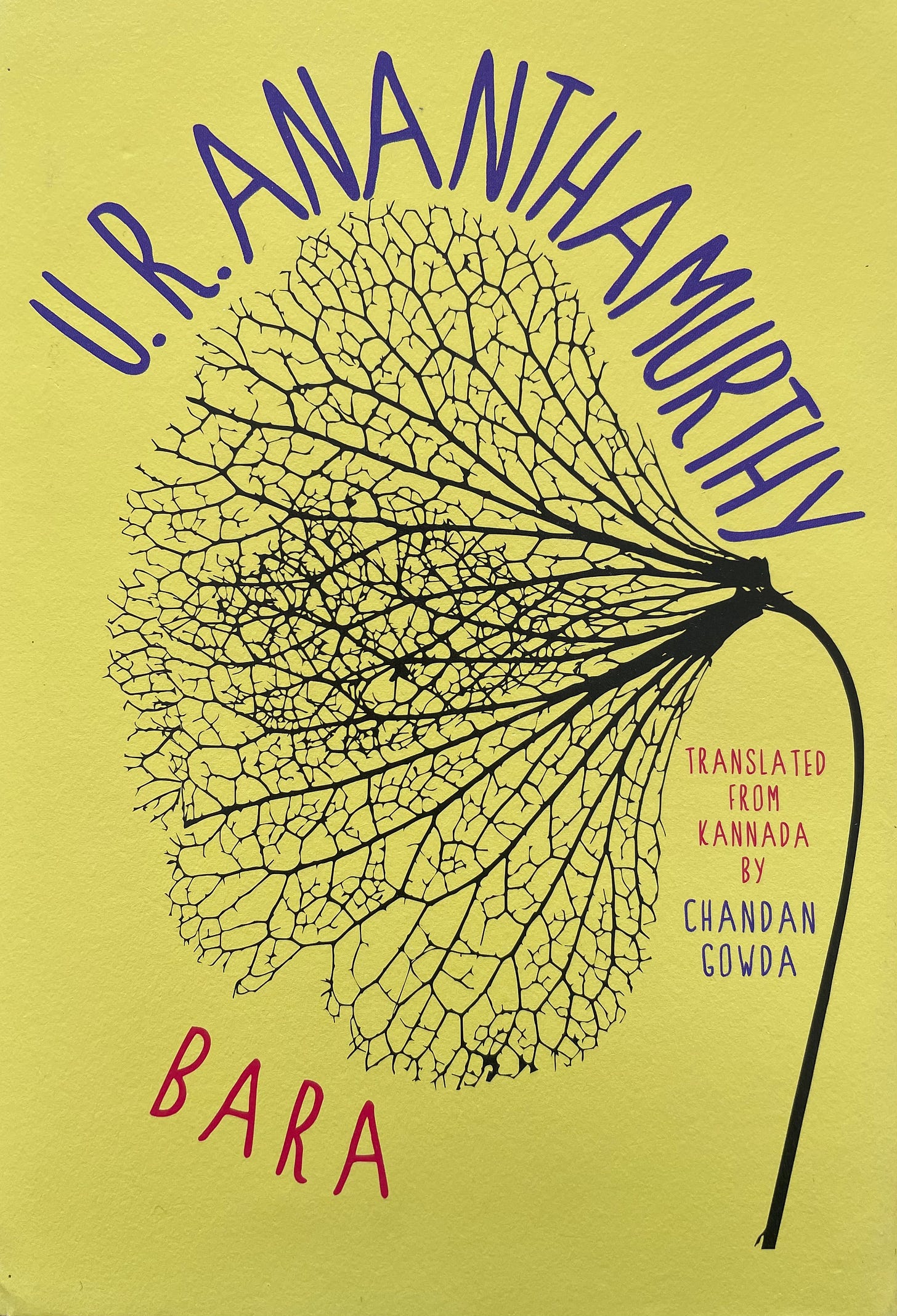

To me this seemed like quite the paradox. How could something surprise and yet seem entirely natural to a given situation? When I read Bara, the late U. R. Ananthamurthy’s short story translated by Chandan Gowda from the Kannada, I felt it had all the qualities Baxter was talking about. Bara is a riveting story with an unexpected, yet inevitable, ending.

Bara was published in 1976 and it also received acclaim when made into a film (in both Kannada and in Hindi). In 2016, it was ultimately published by Oxford University Press as a book. Bara is just some 65 pages in all. But it will have you all coiled up in debate—with yourself and with others. If it’s a book club choice, I wish you good luck for it may be one long evening of arguments and defensive stances.

Bara’s protagonist is a bright Indian civil servant, Sathisha, who grew up in an affluent milieu. He could have pursued a career in any discipline but he chose to enter the civil services owing to a genuine interest in serving the country of his birth. All the ideals he grew up with and even practiced as an administrative officer are challenged when he opts to become the district commissioner in a village broiled by drought. There, in a place that is ravaged by nature, Sathisha believes he can make a difference because of his interest in serving the people. His wife supports him and they leave a lush life of luxury and comfort in New Delhi to enter a life in a drought-stricken village.

In their new abode, an exotic palace once occupied by a nawab, they’re surrounded by a—dry—moat. Just across the moat is the village. There, in a district thirsting for water and grain, throats are parched and nerves are frayed. One man is hoarding rice. The hoarder, Gangadhar, is in cahoots with the district minister who happens to be the arch enemy of the state’s chief minister. In this volatile political climate, Sathisha needs to make choices that can be tantamount to a drop of water or a spark from a matchstick. He can mollify or incinerate. The choices Sathisha makes and his state of mind as he makes them animate Bara.

One day Satisha has the chance to help alleviate the frustrations of the villagers. Right when the opportunity presents itself, his car is also soiled by a bunch of village children. In disgust Satisha drives off, leaving behind many villagers who had been waiting to air their grievances and sorrows to him, their commissioner. That scene in Bara is masterful. The sound and fury of a car whose horn goes off endlessly, thus scaring the children who’ve climbed into it through an open window feels unreal, yet it’s a scene that seems believable deep in a village in India where a fancy car is still an unidentifiable object from an alien planet.

It’s a moment that’s revelatory—to Satisha himself and to us. His possession is disrespected and he’s, quite naturally, upset. Still, his feelings and his demeanor upon the discovery of the dirty car seals his fate in that one moment. What could have been a moment of glory is, instead, the beginning of the end of his political dreams.

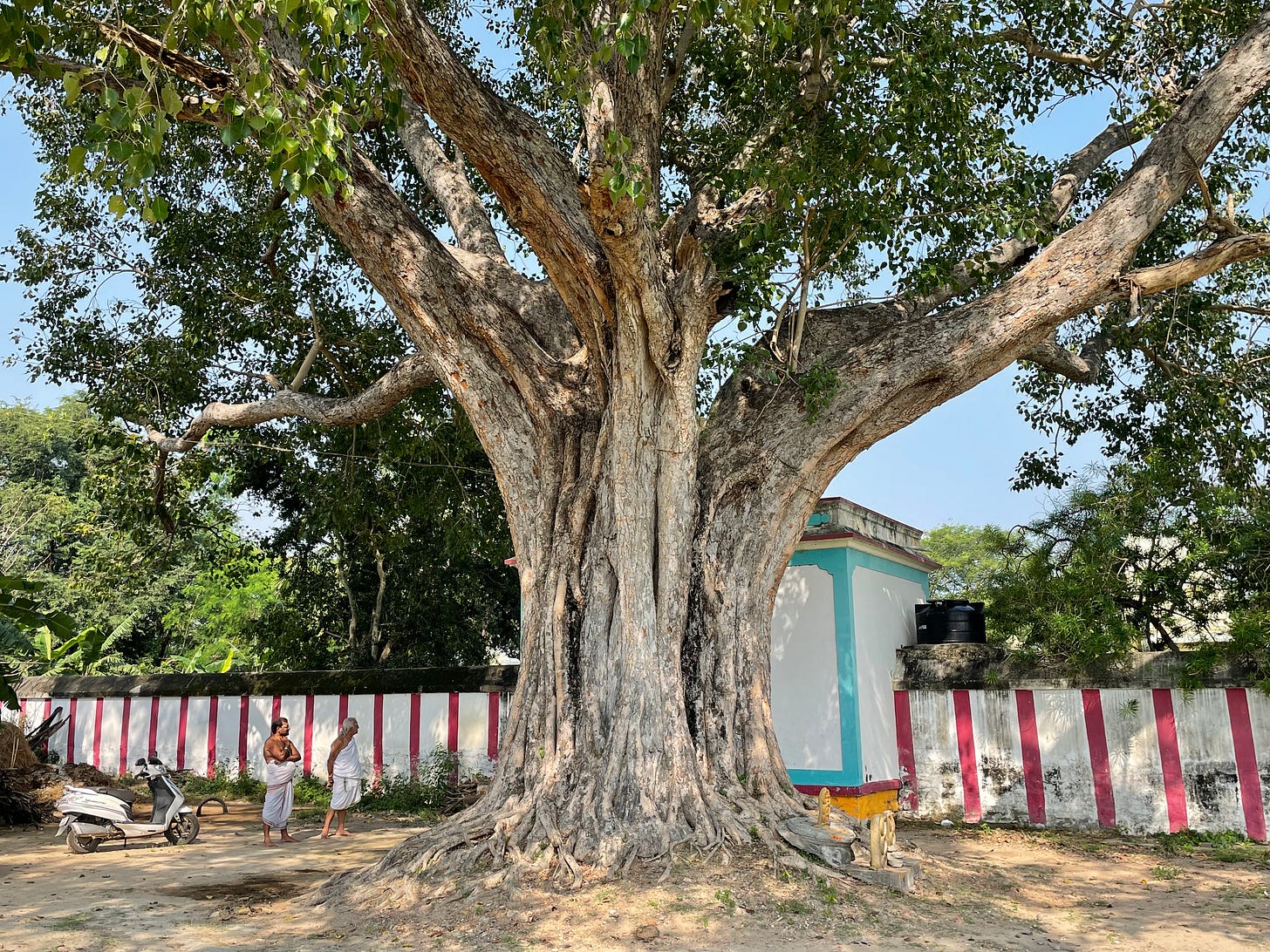

The title of the story, “bara”, means barren or bone-dry in Kannada. In my mother tongue, Tamil, compassion is equated to “moisture”; someone who’s stone-hearted is referred to as not having an ounce of moisture in him or her. A life of service is only possible when there’s a little moisture in the heart. In the end, Satisha and his wife are shown to be devoid of empathy, just as the ministers, the hoarder and the superintendent of police.

It’s easy to spout idealism from the security of an air-conditioned home. But what exactly are your values when you’re languishing in arid heat? That is the question Bara asks of all of us. It asks questions about the privilege of idealism when viewed from the ramparts of a good life. What are your politics? How do your politics change as you age? How far are you willing to go to uphold your ideals? Just when do people with progressive politics become conservative? When it begins to hurt their family? Bara also asks some other questions that made me wonder about me, my husband and my children. At every point in our lives, we make a choice. At some points, the choice that seems best is in direct contrast to the ideals that we once set out to uphold.

Chandan Gowda’s translation was an effortless read. To appreciate Bara, however, I needed the patience to understand the tangled moral worlds of rural life. Most writing in English in India tends to depict urban scenarios and hence I’ve found reading regional writing rewarding. The older I get, the more I want to lose myself in India’s hinterland.

I have on my bookshelf a book titled A Life In The World. Conceived after Ananthamurthy fell seriously ill in 2012, this book shows Chandan Gowda engaging the writer in a vast and thoughtful exchange. One interview in it is titled India’s Political Life. The late Ananthamurthy pondered many issues skewing the world. Among them was the notion of a society versus a nation, the pros and cons of industrialization and the lessons urbanites could learn from the ways of tribals, especially about living in harmony with nature. He poured all his thoughts into the crucible of Kannada fiction. Thanks to translations, we can now peek into worlds that we may never otherwise have entered.

I was forwarded this review by Shyamala Raman, and I'm so she did! I thoroughly enjoyed reading your review. Years back I read what is probably Ananthamurthy's best known book, Samskara, and loved it. Alas, I have no idea who translated it which is sadly the fate of most translators who remain unknown and largely unlauded. That is changing now, and thank goodness for that. It's great that you are doing this series, giving both translators and translations their due. I'm definitely going to read Bara now.