AN ENGLISH PICK FROM MY TRAVELS

During a road trip through the southeastern states, I picked a book published in 1861 by Harriet Jacobs, a former slave girl.

In more ways than one, this is a transitional year for me and it has already begun to reveal itself in the appalling inconsistency of my posts. I had said I would be writing about a short story in translation once a week but that has been rendered more and more challenging by the exigencies of my life.

In early March, when we had to be in Tampa and in Brooklyn during two consecutive weekends, my husband wondered whether we could squeeze in a road trip by bookending the two places. It became a tight squeeze of a trip during which we, most ironically, passed through a town called Tightsqueeze in Virginia. So there I was trying to squeeze it all in, my book plans shelved yet again, embarking on a huge road trip up and down the east coast of the United States.

Before I begin, let me say that this post is not about having read a work in translation. It’s about a powerful book I read while I was on this 3300 mile road trip. Our stops on the drive from Tampa to Brooklyn, NY, were Savannah, GA, Charleston, SC, Durham, NC and Fredericksburg, VA. On the return to the south, we drove through Charlottesville, VA, Asheville, NC, Montgomery, AL, and Tallahassee, FL. I mention these stops because they led directly to the heartbreaking book I ended up buyin in the Charleston museum that was once the mart where slaves were bought and sold like grain and potatoes.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Ann Jacobs was published in 1861. Using the pen name of Linda Brent, Jacobs delineates the lives of African Americans in the southern states in nineteenth century America. This book is about extreme suffering. Every page of it is about the arduous and prolonged suffering of enslaved African Americans in America’s southern states barely two hundred years ago.

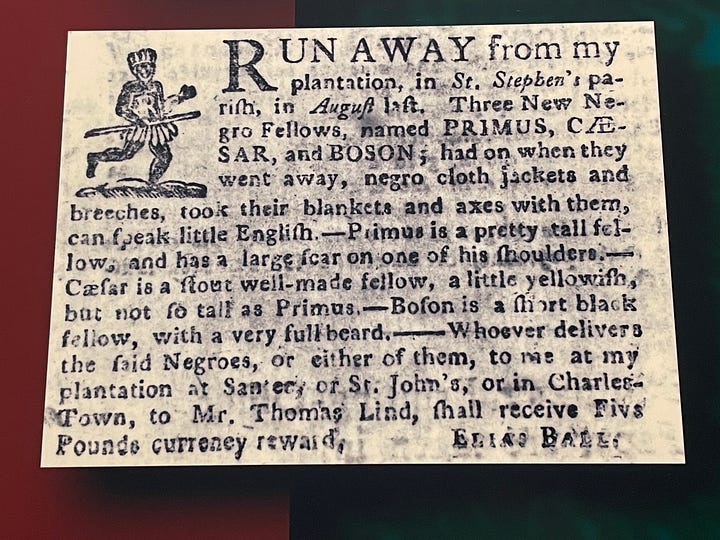

While I was fairly knowledgeable about the African American struggles of the last several hundred years, spending time at the museum that was once Charleston’s Slave Mart was a unique—and chilling—experience. Human depravity at its worst was on display.

January 1st, a momentous day in most of the free world, was a dreaded day in the life of a slave.

But to the slave mother New Year’s day comes laden with peculiar sorrows. She sits on her cold cabin floor, watching the children who may all be torn from her the next morning; and often does she wish that she and they might die efore the day dawns. She may be an ignorant creature, degraded by he system that has brutalized her from childhood; but she has a mother’s instincts, and is capable of feeling a mother’s agonies.

The enslaved life is described in excruciating detail at this Charleston landmark. What happened when a slave owner died, an event that was often the most harrowing in the life of enslaved people? The entire family of slaves working for the deceased owner was often auctioned off at the slave mart. This meant that the family members would never ever see each other again. Through Jacobs’ poignant words we begin to learn how a slave girl in a family is born with the welt of ankle chains right from the day of her first wail.

She will become prematurely knowing in evil things. Soon she will learn to tremble when she hears her master’s footfall. She will be compelled to realize that she is no longer a child. If God has bestowed beauty upon her, it will prove her greatest curse. That which commands admiration in the white woman only hastens the degradation of the female slave.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is thus a haunting account of Jacobs’ life as a slave in North Carolina and of her ultimate escape and emancipation. We learn about the extraordinary resilience of the human spirit; the “Linda” of the story will not be vanquished, even if her muscles atrophy as she hides in the crawl space of her grandmother’s attic for seven long years.

Southern women often marry a man knowing that he is the father of many little slaves. They do not trouble themselves about it. They regard such children as property, as marketable as the pigs on the plantation; and it is seldom that they do not make them aware of this by passing them into the slave-trader’s hands as soon as possible, and thus getting them out of their sight.

This ugly truth that rich slave owners often had a brood of children by their slaves is discussed at length in Jacobs’ memoir. One of the preeminent slave owners in America was, of course, Thomas Jefferson, a Founding Father, author of the Declaration of Independence, and the third president of the United States.

While in Virginia’s Charlottesville, we spent a good part of the day at Monticello, the primary residence and plantation that Jefferson began designing after inheriting land from his father at the age of 14. I found Monticello endlessly absorbing (and upsetting) because the guides were able to tell us more about the man wearing the mantle of statesman.

We saw Jefferson, the uncannily brilliant engineer, architect and scientist. We were always shown Jefferson, the meticulous accountant and bookkeeper. We saw him as a 33-year-old thinker drafting the document that would become the Declaration of independence. Above all, we saw the statesman in all his hypocritical stances, the gentleman who spouted his philosophy about the equality of all human beings while possessing 607 slaves. Under the shade of mulberry trees, we walked through the slave quarters and plantation, and discovered what it was to be worked to the bone in the fields at Mulberry Row and at the weaving looms or at the tool sheds.

Working at the plantations was often the most dreaded of occupations for a slave and Harriet Jacobs talks about the iniquities that she was privy to regarding life in a plantation.

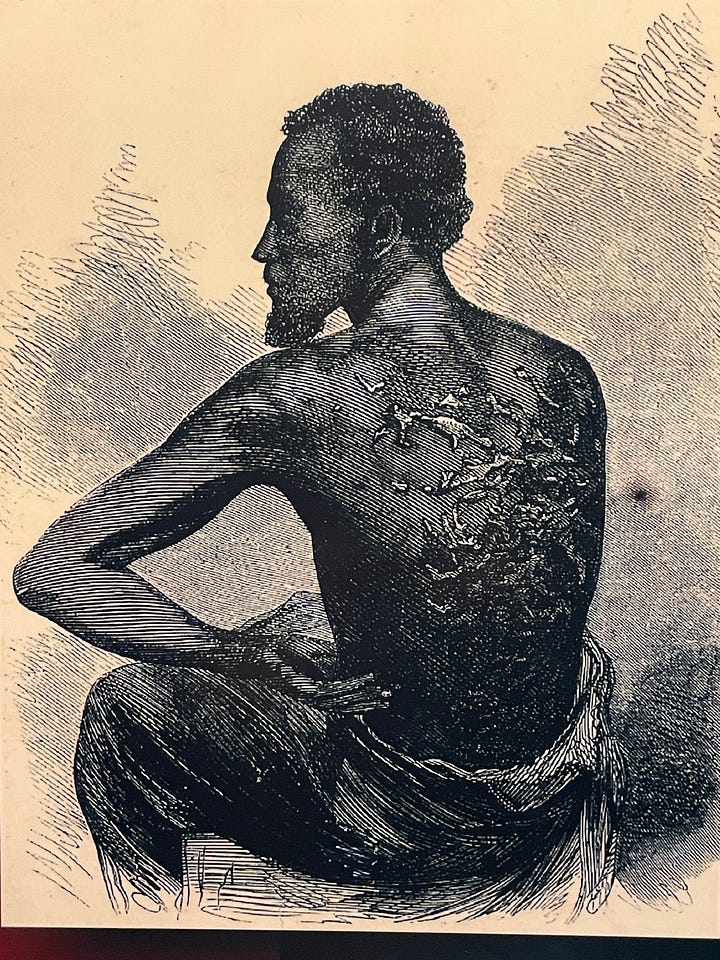

If a slave resisted being whipped, the bloodhounds were unpacked, and set upon him, to tear his flesh from his bones. The master who did these things was highly educated, and styled a perfect gentleman. He also boasted the name and standing of a Christian, though Satan never had a truer follower.

For me a personal highlight was Alabama’s Montgomery where we spent two hours at the Rosa Parks museum. Montgomery traces its history to the early 19th century, to the war of 1812 and the industrial revolution. Millions of acres of land were ceded to the United States, with much of the land sought by speculators. There’s a term called “Alabama Fever,” apparently, and this frenzy—around the time of California’s Gold Rush—related to the lands of the Big Bend of the Alabama River that were celebrated for their rich soil. Cotton was “king” in those days and thanks to the industrial revolution, Montgomery flourished as both a trade and transportation hub. Its central position at the head of steam-boat navigation, together with its late railroad connections, made it a center for cotton and other trade.

As my husband flew over country roads in Alabama and Georgia under the shade of the most spectacular green that embraced over our heads, I thanked god for delivering us safely at Orlando airport. We had clocked over 3200 miles and seen and heard so much.

There’s another worthwhile book I must mention. For a few years now I’ve been reading Jill Lepore’s These Truths, a fascinating account of American history told over some 800 pages. That sort of reading is a multi-year project, however. A way to supplement this effectively is always by travel.

The town of Selma felt grim and foreboding during my trip. A local gentleman asked me if I felt like time itself had stopped in Selma, that it was as if it were in a time warp from the 60s. It hadn’t grown into today, I realized. Perhaps it wasn’t allowed to grow? “There’s no theater or bowling alley, nothing!” The man said to me. “Which young person wants to live here?” When I heard that after all these years the state government would not rename the famous bridge (it’s currently named after a general in the Confederacy), it’s impossible to discount the victories that have indeed been won in the past. A small, unpretentious museum called the National Voting Rights Museum greets visitors on the other side of the bridge reminding us of all that has been won and of all the truths that we must hold dear.

This is a great article - I'm adding it to my LONG list for favorites (that you have written, and shared with us). Thank you.