ABOUT THAT AUNT WHO WOULDN'T DIE

This matchbox of a book is still topical. Why can't things be different for women?

Once in a while something happens that paints my day in luxuriant colors by sending me an affirmation about my work. Last Sunday, a writer and artist by name Peter Moore recommended my newsletter. Check out Peter’s Substack presence. Road2Elsewhere is hilarious, thought-provoking and entertaining. Here’s what he said about my work.

“Those of you with a literary bent will enjoy this weekly tour through a translated work from strange and interesting lands. This week it’s Noh poetry, but there’s no telling what Kalpana will find next. She reads so you don’t have to. But I’m guessing you’ll probably want to.”

Peter is right about one thing. There’s just no telling what I’ll find next. While I maintain a weekly list of books of must-reads for the year, I don’t seem to be able to stick to it. Instead I wait until Monday for inspiration to arrive.

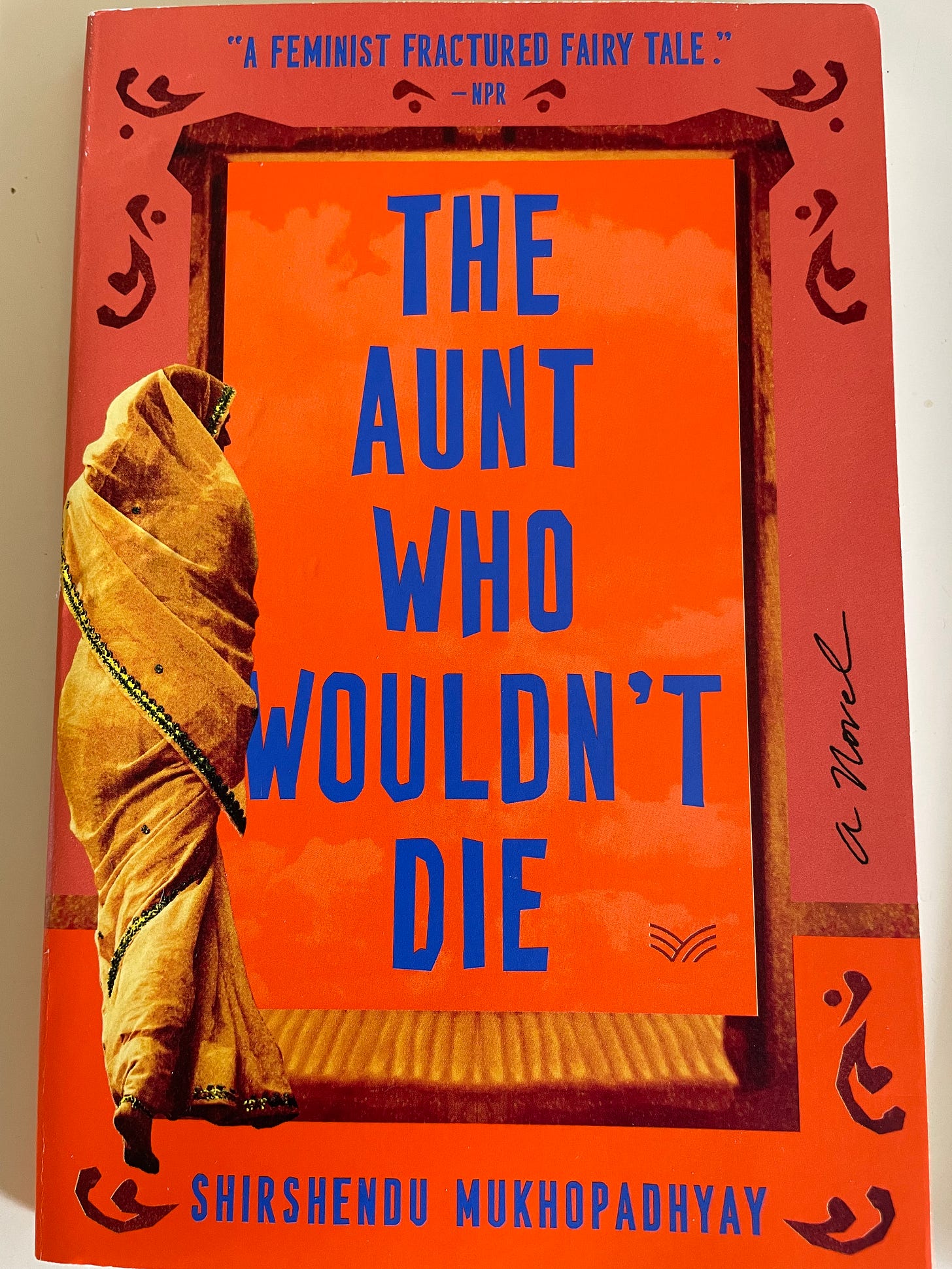

This week I felt the pull of the novella titled The Aunt Who Wouldn’t Die, a book that was recommended by NPR two summers ago. Which of us hasn’t had an old someone who wouldn’t die—after they had actively begun to do so? When my parents were in their death bed we prayed for their end to be swift and painless. Unfortunately, the process of dying holds even more surprises than the process of living itself. Those of us who have shepherded our loved ones through to the other world have wondered about that space in between.

Long after my parents are gone, I feel their presence. Yesterday, my late father spoke to me from the pages of a prayer book into which he had tucked a slip of paper with a list of Sanskrit words and their meanings. I’ve often sensed his sprightly gait in the flitting of the grass yellow butterfly at Jeeva Park (his daily haunt) in India’s Chennai. I’ve heard my late mother’s remonstrations in my ears when I found myself taking a short cut while making a dish that was once her forte.

Hence, when I was buried in the pages of The Aunt Who Wouldn’t Die, I accepted everything that happens in the tale as if it were the most natural thing in the world. The magical realism of this work couldn’t have been more organic to the story, just as the visitations of the ancestors of the Buendia family in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

Where Garcia Marquez’s sentences are intoxicating, loopy and long, Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay’s are sparse, blunt and punchy. Considered one of the finest writers of modern Bengali literature, Mukhopadhyay is a prolific author of both adult and children’s fiction. The Aunt Who Wouldn’t Die first appeared in 1993 and it became a classic that went on to grace the silver screen. Translated into English by Arunava Sinha whose transcreations I find infinitely readable, The Aunt Who Wouldn’t Die ends in an abrupt fashion, hinting at the possibilities open to a privileged young woman in India at the end of the 20th century. I turned the 141st page only to come up against a blank ghost of a page.

In this novella, the ghost belongs to an angry, embittered aunt (in Bengali, “Pishima” refers to a father’s sister)—who was unfulfilled during her life on earth. When a girl from a poor family, eighteen-year-old Somlata, marries into the Mitra family—a noble Bengali household in a palatial home whose descendants pawn off the family gold to keep up appearances—she must decide how much she should heed the words of Pishima’s ghost.

When Somlata walks into the abode of her new family, she notes that everyone is afraid of Pishima. It isn’t until the harridan dies, however, that Somlata realizes why Pishima was even tolerated while she lived. No one in the family mourns her death. Instead, as soon as they know her body is stone cold, they begin looking for a certain box that once belonged to the old woman and has been under lock and key in Pishima’s room. Everyone in the Mitra family, even the servants, wants to know where the box is.

After a few minutes of silence, he said, “Pishima’s jewelry box couldn’t be found.”

A barrel of blood spilled in my heart. “Jewelry box?” I asked in a quivering voice.

“Yes. Not a joke. A hundred bhoris of gold. Some forty or fifty pure gold guineas alone. Pishima’s dowry.”

I was surprised. That was more than a kilo of gold. How had I managed to carry such a heavy box downstairs?

This is such a delightful, mordant tale that I wish I could share the entire story here. Instead, I’ll dwell on the takeaways, many of which are invaluable even in these different times in India. It’s unfortunate that the legacy of patriarchy and female oppression is not behind us in the country of my birth or in my adoptive nation.

With Pishima’s death, the Mitra family begins to realize that the money they had thought would come to them remains elusive. Should they pretend to be who they used to be or should they step down from the pedestal of their “noble” pedigree, marshal all their resources, open a retail business in town and embrace the dignity of labor? Somlata, who did not grow up with the trappings of privilege, shows the family another way to resurrect their social prestige and dignity. They realize, very soon, that the town that gossips behind their backs when they run out of luck, can rally around to support them when their business turns a profit.

I was moved by how Somlata manages to bring about extraordinary changes among the arrogant members of the Mitra family. She never loses her composure even when she’s almost strangled by a human or harangued by a pestilent ghost. Her views on taciturnity are lessons in how to zip our lips at delicate moments.

“I didn’t know what to say. Most people are in the habit of saying unnecessary things even when there is nothing to be said. I don’t have that habit. I never speak when there is no need to. This time too I didn’t try to defend myself or allay her suspicion. I knew she wouldn’t believe me no matter what I said.”

Like the ghost, the book too drills down to the point on every topic. There’s a rib-tickling passage in which Pishima’s ghost wants to know more about sex. This is a more unsated, vile-tongued ghost than any I’ve encountered in fiction.

One day Pishima asked from the shadows where she lurked, “How does it feel, eh?”

“How does what feel?” I asked.

Pishima said with a touch of embarrassment, “Don’t pretend you don’t understand. All those things you do with your husband, what else?”

“Shame on you, Pishima.”

“Ish, what a shrinking violet. Is it a crime to ask? Married at seven, widowed at twelve. I wasn’t even old enough to understand. By the time my body woke up my hair had been cropped and I was reduced to one meal of rice a day and fasting on Ekadoshi. How will you understand what I went through? Tell me what it’s like.”

“It’s good.”

“Damn you, you bitch. Everyone knows it’s good. Give me details.”

I found The Aunt Who Wouldn’t Die most memorable for how it’s unafraid to tackle women’s issues. With Pishima’s character, Mukhopadhyay represents all those widows left behind by the wicked Hindu patriarchal system of yore whereby widowers could remarry but widows could not. Hindu society had long disallowed the remarriage of widows, even child and adolescent ones, all of whom were expected to live a life of austerity and self-sacrifice. Relegated and cursed by the husband’s family, these young widows were often forgotten by their own families too.

Mukhopadhyay’s work celebrates three generations of women. By the time we reach the end, it’s clear that the youngest generation has all the choices that were never open to the two earlier generations. All three women possess a certain strength of character. In the youngest, Boshon, the only child of Somlata, we see the spirit of defiance. She won’t settle. She asks questions. She’s unafraid of societal mores, unlike her mother who walked the fine line between accommodation and resilience. We begin to admire the power of Pishima’s vitriol and intransigence and realize that that effrontery is the surest fix for a hidebound society.

The story touches upon another point that gets discussed a lot in the present day—the lack of sisterhood among women. Women, they say, are catty, emotional and competitive. What holds us women back, apparently, is the oneupmanship we display in order to prove our superiority over other women. What if women actually worked in tandem with other women? What if women worked more subtly—and more generously—for the greater common good? The Aunt Who Wouldn’t Die shows us the possibilities.

Quite Gripping Kal. At this rate Oprah is going to contact you soon . You have captured the essence of the book so well. So proud of you!

I for once am speechless. Thank you for lovely shoutout above. But more than that, thank you for the exploration of complicated sisterhood. What if women worked in tandem, and men supported them in their achievements, to the benefit of all? Not sure we’ll ever reach that world, but some of us can create it in miniature. And read about it! Or at least, read others who have read about it!