A WRAITH OF THE PANDEMIC

A 1940s novel about the plague kindled many feelings from the recent past.

I was in the “Used Books” section of Book Passage in Corte Madera a few days ago and as I began to read the first page of this 1948 translation (by Stuart Gilbert) of Albert Camus’ La Peste, I was transported to the terrifying daily news bulletins of early 2020. I really did not want to live through that horrific time, yet the opener was powerful.

In any event, where would I ever find this brand “new” used classic for $4? Acclaimed when it was published in 1947, The Plague is supposedly an allegory of France's suffering under the Nazi occupation as much as it is a compelling tale of man’s determination and resilience against the fragility of his existence.

“In the mornings the bodies were found lining the gutters, each with a gout of blood, like a red flower, on its tapering muzzle; some were bloated and already beginning to rot, others rigid, with their whiskers still erect.”

As I delved deeper into The Plague, I realized that this line was prescient. It’s as much about the humans as it is about the rats that are the harbinger of an epidemic that rattles the Algerian coastal town of Oran.

I’m yet to finish reading this book, unfortunately. Over halfway through the book I can vouch for how the book resonates with me more than seven decades after publication. I’ve underlined page after page of quotable passages. Camus describes life in the city right after the onslaught of the plague. He notes that spring is making its progress into the town. Nothing has changed. Yet everything has.

Thousands of roses wilted in the flower-venders’ baskets in the marketplaces and along the streets, and the air was heavy with their cloying perfume.

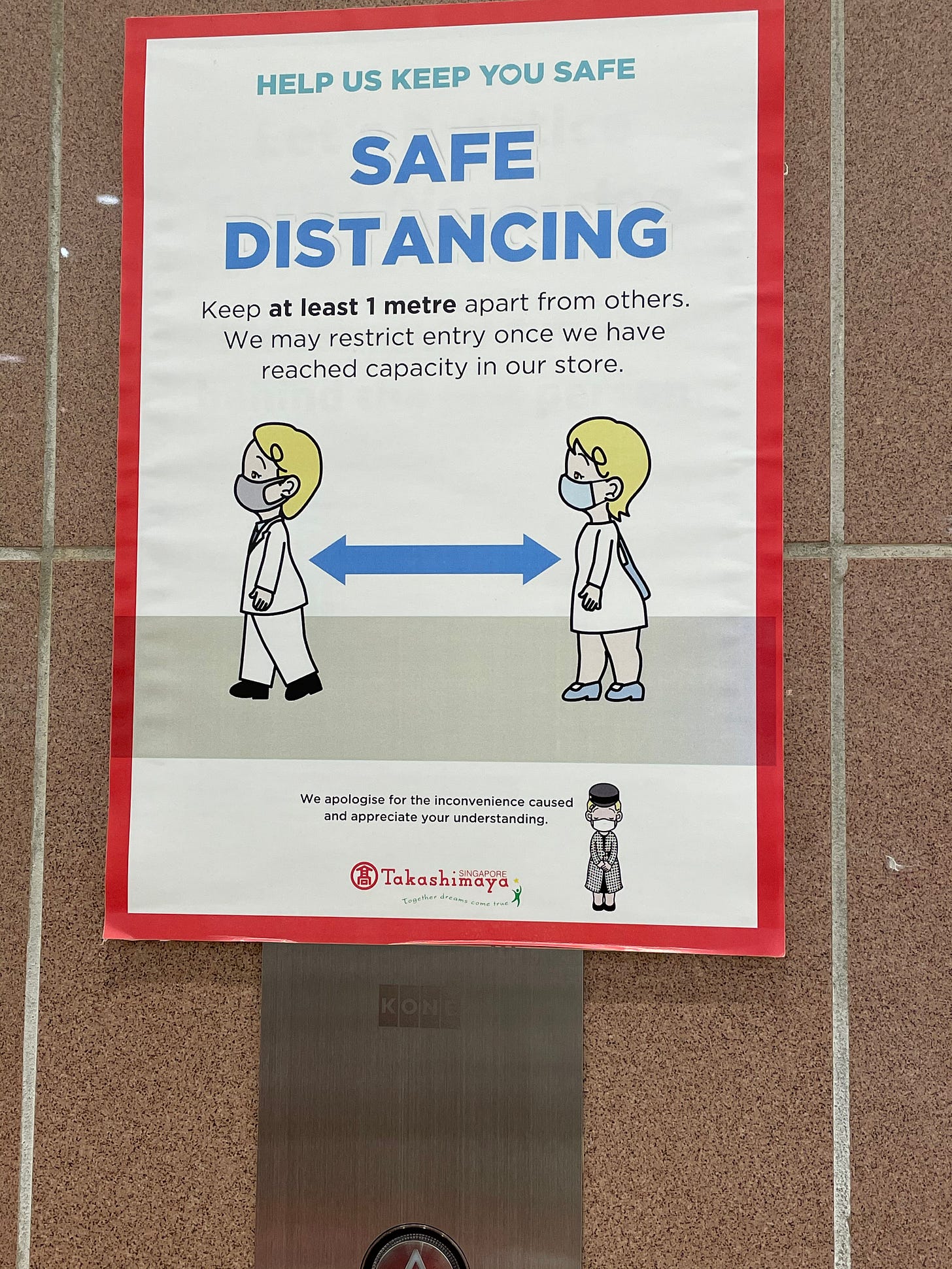

Even as the city of Wuhan went on lockdown in December 2019, I was in Singapore on a short holiday. The buildup of anxiety was palpable. Yet no one seemed unduly worried. Months later, everything changed. Just like the characters in The Plague, I found myself in a government-ordered two-week quarantine in Singapore in December 2020. I was frustrated with the constant monitoring by the ministry of health. No one wants to be told just how to be. In The Plague, the people of Oran do not like being walled in.

Early on in the novel we meet Dr. Bernard Rieux, a man whose compassion devolves, over time, into steely indifference towards the patients suffering from the disease. He’s pragmatic and determined, and expects the people in positions of power to do the right thing: “The language he used was that of a man who was sick and tired of the world he lived in—though he had much liking for his fellow men—and had resolved, for his part, to have no truck with injustice and compromises with the truth.”

As I watched Dr. Rieux manage his patients and keep count of the dead week after week, it was hard to not recall the comportment of Dr. Anthony S. Fauci, Chief Medical Advisor to the President of the United States. Rieux’s pointed corrections of people—in positions of authority as well as ordinary citizens—are not unlike Fauci’s constant reminders on television of the science behind the coronavirus, its dispersion in the public domain and his words of caution to the general public.

Camus wrote The Plague over 75 years ago. The plague is almost eradicated today; even though we hear about a rare outbreak of the plague in some parts of the world, it’s almost never fatal. It’s clear, as I plow through this book, that what has not changed, however, is human arrogance and complacence in situations that call for caution, courage and equanimity.

I will always remember how the coronavirus pandemic underscored the best and the worst attributes in human beings. In this novel about the black death, too, we see many incandescent and wretched moments.

We are told the story of a grocer who piled up masses of canned provisions with the idea of selling them later on at a big profit. When the ambulance men came to fetch the grocer they discovered that he had several dozen cans of meat under his bed. Cottard, a raconteur, tells Dr. Rieux the grocer’s story. “He died in the hospital. There’s no money in plague, that’s sure.” In recent times, it’s hard to forget our many trips to Costco or our local Safeway grocery store during Covid-19 only to discover that while people were dropping like flies, some people were so worried about their rear ends that they hoarded toilet tissue.

The reactions of the people of Oran to the announcement of the contagion hardly surprised me. In that fictional world, for many weeks, everyone is in denial; they go about life as if nothing has changed.

In the real world, during the early weeks of Covid-19, the world remained deeply skeptical. The paltering with the truth—regarding the origins of the virus—occupied people’s minds indefinitely. What became a topic of discussion for months to come was the effect of the quarantine on the human psyche.

When the town gates shut in Oran, the plague becomes a concern for everyone. Camus expresses in perfect prose what all of us felt in 2020.

“But once the town gates were shut, every one of us realized that all, the narrator included, were, so to speak, in the same boat, and each would have to adapt himself to the new conditions of life. Thus, for example, a feeling normally as individual as the ache of separation from those one loves suddenly became a feeling in which all shared alike and—together with fear—the greatest affliction of the long period of exile that lay ahead.”

Camus writes about how, in exile, human beings seemed to become different people altogether. What kept us going during 2020 and 2021 was our tendency to seek the sun and take in the bounty of nature. It’s observations about humanity in distress that make The Plague both unsavory and breathtaking.

“Looking at them, you had an impression that for the first time in their lives they were becoming, as some would say, weather-conscious. A burst of sunshine was enough to make them seem delighted with the world, while rainy days gave a dark cast to their faces and their mood.”

I did finish reading The Plague one day after I should have. I’m so glad I persisted. Despite the storyline, this is one of the finest novels I’ve read. The last third of the book is heavy, with its rising death count and its unending debate on faith versus science. Yet, Camus never loses sight of the story itself. Until the end, even as his dear friends vanish, Dr. Rieux always remains wary, yet hopeful. The closing lines of the book must be engraved in gold for, as Dr. Rieux observes, “the plague bacillus never dies or disappears for good” and “perhaps the day would come when, for the bane and the enlightening of men, it would rouse up its rats again and send them forth to die in a happy city.”

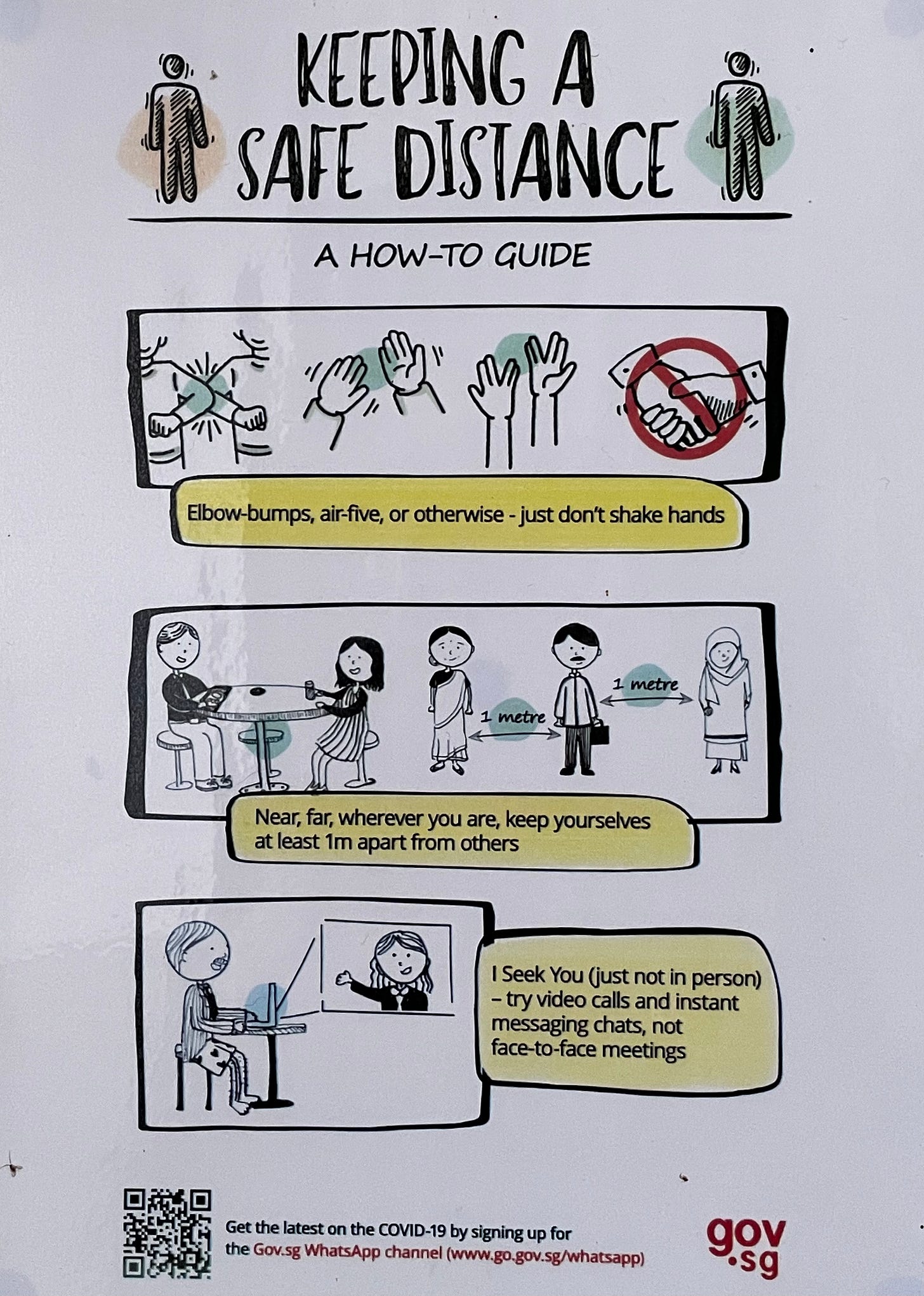

I love the wording from the public health sign: “I seek you.” Isn’t that the human condition? Seeking, and hoping to be sought. Even during plague, when contact can be fatal, it persists.

Kalpana, you have captured the parallels between the 1947 allegory and what we ourselves experienced for the past two-plus years with the pandemic well! It sheds light on how human response to these "Black Swan" events is predictable and how we revert back to our instinctive responses in such situations. Thanks for sharing your insights!