A VOICE FROM THAILAND

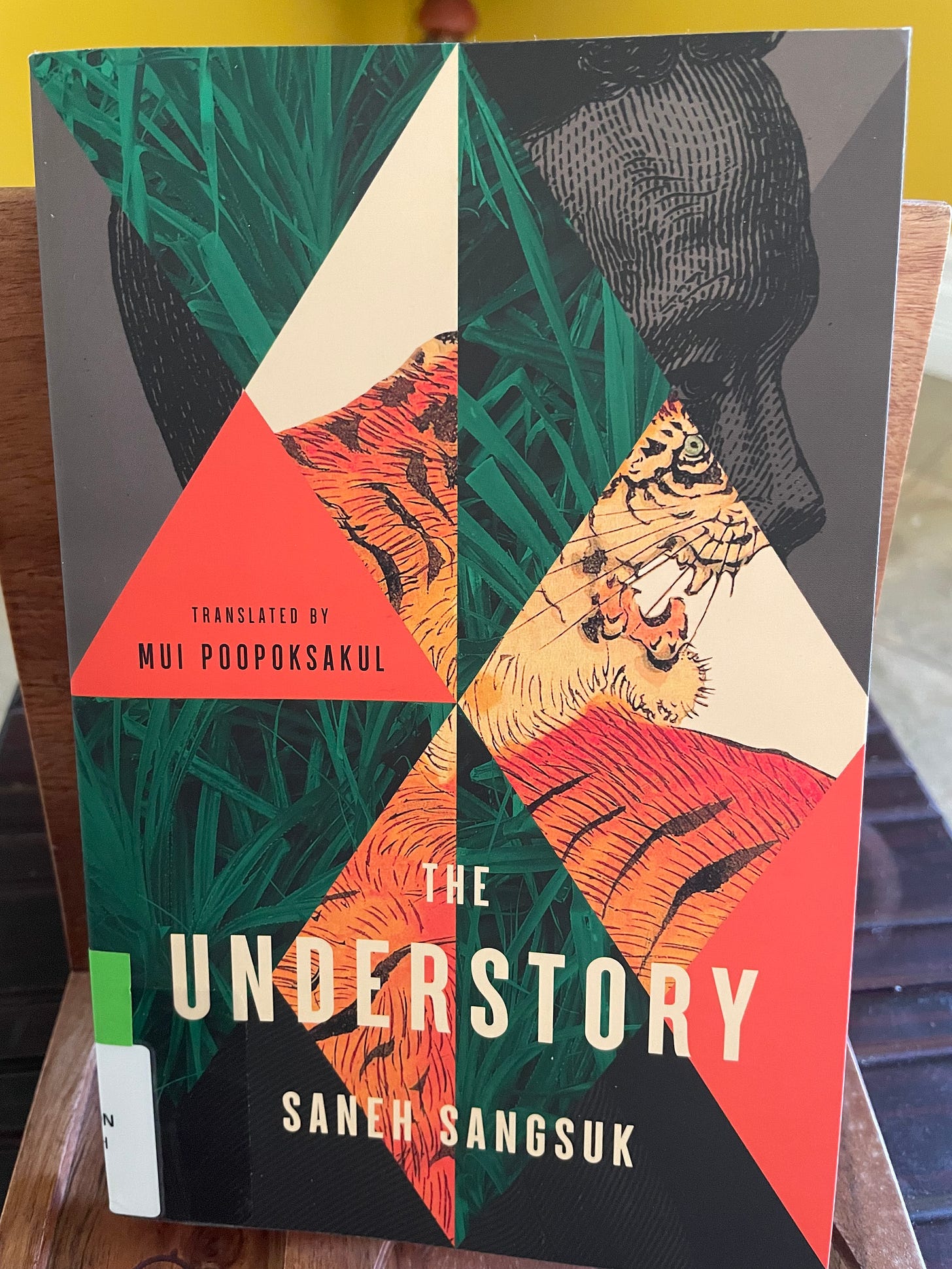

A Thai writer spins the story about a storytelling monk whose stories regale the people of the village of Praeknamdang. As the yarns unreel, we're head to head with the scariest cat of all.

Chances are that when you are about halfway through the Thai novel called The Understory, you will be unable to read on without setting it aside for a few minutes just to steel yourself for what may be coming up next. Saneh Sangsuk’s pen thwacks you with such unexpected ferocity—of language, atmosphere and plot—that you may not eat, sleep or shower during the eight or ten hour time frame during which this book hangs over your head.

No sooner had I opened the novel than I fell in love with the page preceding the opening page of the story. “Literature has nine flavors,” the author writes. He then proceeds to enumerate the “navarasa”—the nine emotions evoked in an audience—that are such a key part of the Indian performing arts traditions. The nine Sanskrit words reminded me of the myriad ways in which we respond to any stimuli with all of our being.

The Understory recounts the story of a man who tells stories about his life. He often launched into his stories by reminding his listeners about how much had changed in just one lifetime. As the novel opens, we are in the Thai village of Praeknamdang which has recently fallen into difficult times. The year 1967 has been a challenging one marked by a flood that devastated the season’s rice crop. The villagers are anxious. Luang Paw Tien, the aging abbot of Praeknamdang Temple, is also worried about his people and the flora and fauna of the land.

Although he was undoubtedly far ripened with age, everybody (other than Luang Paw Tien himself) was of the opinion that he was the most robust old man they had ever met. His hair, eyebrows, stubble, and even the little strings hanging out of his nose were all white, his face was creased and sagging, and he had spots and moles scattered all over his chest, back, shoulders , and the underside of his chin. He had a tall and solid build, which evinced that in his youth he must have been exceedingly strong, though all that remained on him now was wrinkled, drooping flesh. But he still had a full set of teeth, none of which wobbled at all, a testament to the benefit of drinking a tall glass of one’s own urine a day, and his eyes still gleamed in the light of the fire, and his voice was still spry and cheery. He was their monk, and the most senior elder of Praeknamdang, which made all the people revere him, and the grandness of his heart made all of them love him.

Seventy-three years into his monkhood, this ancient man still continues his daily alms walk and “though his body was ancient and he suffered because of his asthma and arthritis, he remained vital enough to walk his alms route into the village nearly everyday, the round trip distance just shy of seven kilometers.” The monk walked accompanied by his beloved ox, Kamin, “who was tame as a dog,” but was stubborn, and hence unwilling to accept food from anyone else’s hand but that of her master.

The old monk entertains the children of the village every night with tales from his youth. He tells them stories about his 15-year pilgrimage to India, his mother’s dreams of a more stable life tilling land for rice fields, and his intransigent huntsman father who refused to farm until his dying day. Then he begins to tell them about the love of his life. As he spins his yarns we are entranced by his mesmerizing voice. What begins as a tale of adventure of a monk’s experience in the jungle takes an unexpected turn.

Luang Paw Tien is no ordinary monk, we soon realize. We begin to peel the layers of the story of a man of extraordinary strength and wisdom. As we journey through his life, it seems that we experience every “navarasa.”

One of our first stops on this adventure is when the 25-year-old novice is huddled under a “glot” (a tent with a mosquito net) in the middle of the jungle in a spot that belongs to a herd of wild elephants. The elephants make it clear that they are not pleased by the tent in their territory and they “formed a circle around his flimsy, puny, defenseless glot as they whipped their trunks high, fanned their ears wide, dug their forefeet into the ground, and trumpeted, the blare coming from them as deafening as if they were a band of great horns playing at full blast all at once; they looked angry, full of menace, full of malice, intent on driving him out of their path.”

We watch the monk shrink in terror. He seeks no recourse but prayer, chanting “Buddham saranam gacchami, Dhammam saranam gacchami. Sangham sranam gacchami” over and over, waiting for the final deliverance even as his head is about to be crushed. Instead, nothing happens even though he feels the chaos outside the tent cloth. Then he peers out.

Peering out through a hole in his canopy, he saw trunks and tusks and forelegs and bellies and hind legs and tails moving slowly, leisurely away. It was a display of enormity so powerful that he felt himself to be a child again, utterly benign, utterly inept, utterly graceless, as he listened to the sounds: the earth rippling like it was liquid; tree branches snapping, yanked down by the elephants’ trunks; the grumbling juices sloshing inside the elephants’ stomachs; shit and piss being expelled without shame or embarrassment; a large tree shaking its branches roughly as one or another of the elephants rubbed itself against the bole to be rid of an itch.

The adventure with the pachyderms is scary indeed but we don’t realize how the terror factor is about to be turned up a notch when we meet the most intimidating cat of all, the tiger. Our monk is a man of the jungle and he teaches us about what it takes for a family to survive in the jungles of Thailand. It’s not just a page-turner for most humans. It’s a stomach churner, too, and I absolutely must not share any spoilers. This is a book for all shelves, a book you’ll be calling others about.

It is a classic tale of man against beast but it teaches us, metaphorically speaking, to bow, if not prostrate, in the presence of a wild animal in the jungle. While reading this novel, we begin to feel an immense awe and respect for nature, and for the hierarchies at play in the wild. We learn that we must calibrate ourselves and never seek vengeance. As in a book titled Vaadivasal that I read many moons ago, it also makes us wonder who the predator is, after all—man or beast?

Saneh Sangsuk’s work, above all, is a lament about the depredations of the jungle by human hands. Luang Paw Tien mourns the inevitability of losing villages and the jungle to capitalistic greed.

Areas that had once been forest land now had owners and had been cleared into planting fields, and the people, both the original inhabitants and the newcomers, no longer lived off the jungle but were farmers and orchardists. He often said that he had not been present to bear witness to the obliteration of the jungle, but it was he who was the last remaining witness to a time when all around Praeknamdang was jungle, everywhere you looked; a time when human settlements had been something foreign, and their accompanying fields, orchards, farms, and paddies foreign land.

If readers pick up this novel to savor the language and taste the incessant drip of honey off each sentence, it will be rewarding. The Understory is so rich in its gifts; it’s a treasure trove for a group reading experience. While one may view it as just a beautiful story, it’s also a parable and a lament about man’s thoughtless depredations and about how not to be. By the time the story ends, we realize that the navarasa opener is symbolic; both readers and listeners are expected to reflect on the negative human emotions that can take a toll on their peace of mind.

This translation by Mui Poopoksakul is such a delight to read that by the last page I knew I had to read everything by the author-translator duo. It must be said that I would have added another “rasa” that’s packed into this reading: tension. As the novel progressed, I found myself exceedingly anxious and tense. The Understory evoked visceral responses in me throughout and when I reached the last page, I believe I felt my heart lurch to a halt.

I think you need to run that "tall glass of his own urine a day" tip by a dentist. I'm not sure that's the key to strong teeth. But I also love the multi-flavor theory of literature. Makes me want a multi-scoop ice cream cone. Chocolate and strawberry, please.

Also read Yaanai Doctor by Jeyamohan in Tamil. Translation also available as Elephant Doctor.