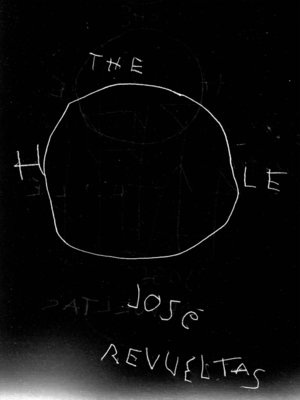

A TITLE TO REMEMBER

From the title to its lurid contents, this novella is one endless rant about voices trapped and crushed by the fetters of society.

I’ve had too much on my plate in the last many weeks and hence reading has suffered tremendously. Every unexpected speaking opportunity seems to have packed itself into the months of October and November. Besides, travel to Mexico City for a wedding was thrown into the mix, too.

I can’t complain. The destination wedding was as much of a dream come true for me as it was for the bride and groom, and my husband and I decided we’d simply travel ahead and enjoy the city before the wedding festivities began. What we didn’t realize was how wildly the city would be decorated for the celebrations for El Dia de Los Muertos. We had no idea, until last week, that Mexico City was home to 173 museums. I don’t believe I’ve been inside a more creative and original space than the Museo Nacional de Antropología.

This week, I had to choose one of the books I bought in Mexico City—for a sum that shocked me after the purchase, upon dutiful conversion from pesos to dollars by my husband. Not only are translations expensive to buy, it seems they’re rare commodities in Mexico. When I visited Under The Volcano Books in the Cuauhtémoc area of the city, I learned that there simply isn’t enough demand in the city for works translated from Spanish into English. It’s such a pity because the two books I bought are punchy and potent. I wrote last week that The Houseguest And Other Stories by Mexican writer Amparo Dávila was such a dazzling read even though it was creepy and scary in parts.

My pick for this week, The Hole by José Revueltas, is both riveting and revolting. This author and journalist (1914–1976) was a lifelong political dissident and hence was incarcerated at many different points in his life for his writings. At 14 years of age, Revueltas joined the Mexican Communist Party and was twice imprisoned at the penitentiary at Islas Marías. Los Muros de Agua (1941; “Walls of Water”), his first novel, is based on incidents that occurred during his confinement. In 1943 Revueltas was expelled from the Communist Party and took part in founding the Spartacus Leninist League. He was arrested for his role in the student disturbances of 1968 and was briefly imprisoned at the penitentiary at Lecumberri.

In the late ’60s, he spent two and a half years as a prisoner at Lecumberri and it became the setting for this novella, which, on many levels, is probably fitting also for another celebration in the Hindu tradition: Diwali, celebrated today by Hindus around the world, is often similarly timed with The Day Of The Dead celebrations. The Hole is like the Sutli bomb once used for Diwali celebrations in India.

A classic of Mexican literature in the twentieth century, The Hole follows moments in the lives of three depraved inmates as they plot to sneak in drugs under the noses of their “ape-like” guards. While the guards believe they’re safeguarding animals, it seems that the guards, too, are as wild and “trapped on the zoological scale'“ as they come. It’s clear they are all in prisons of their own making.

Apes, arch-apes, stupid, vile, and naïve, naïve as a ten-year-old whore. So stupid they didn’t seem to notice that they alone were the captives, they and their mothers, and their children and the forefathers. They were born to keep watch and they knew as much, to spy, to constantly look around, making sure no one escaped their clutches in the city…

In the meanwhile, when the story begins we see that the inmates (Polonio, Albino and a third man whom we only know as “The Prick”) desperately need drugs to keep them tethered to their hellish life. They hatch a plan that involves convincing one of their mothers to bring drugs into the prison.

The woman whom they choose to carry out the mission is an older woman, a dull, unattractive “mother” whom the guards will not care to search, the woman who gave birth to the man they’ve labeled “The Prick”. She is the anointed one, the one who will carry the drugs deep inside her as she enters the prison; her two “hot” young friends, Meche and La Chata, will distract the guards as they manage to pass by the cell where the inmates are housed

"The thing was just there, inside her, something material. Polonio described it as a cotton plug attached to a thread about twelve inches long…”

While reading this novella, we realize how the title works on so many levels. The “hole” is the prison, of course, but it’s also that black hole in which things go, never possibly to return. It alludes, specifically, of course, to the vagina, the place where the drugs are expected to be held, the place that also birthed the most vile of creatures called in life as “The Prick” who is always cutting himself by making holes in his body to stay sane and rooted..

“The hole” becomes the author’s refrain, with his multi-faceted references being as brutal as they are brilliant. This novella is believed to be an allegory for the ways in which a government clamps down on dissent and hauls protestors into places from which they may never return, black holes that are meant to gobble up people’s identities and spit out automatons without any individuality or purpose.

The Hole is a disturbing read and it behoves us to stay focused on the page, giving readers no breather whatsoever. The words gush forth in an unending torrent, challenging us often to enjoy—and recoil at—the stunning turns of phrase. This renegade writer describes a prison inside a prison, warning us about how dissolute institutions merely engender more depravity and deviance.

I admire your tenacity in continuing through such difficult reads! Prisons do seem to be depraved institutions that make all involved depraved - guards, inmates, and their families…

Difficult to even read ABOUT this novella, much less crack it open myself. Thx for sparing me. I’ve coined a word to encapsulate this book: riveting + revolting = rivolting. Ugh.