A PAST THAT IS NEVER TO BE

This second novella by Stefan Zweig had me pinned to the book, like iron to magnet. If what we once had can never be, will we ever make peace with ourselves?

I don’t like to read an author again within a matter of just a few weeks but when I happened upon Stefan Zweig’s Journey Into The Past last week, I was hooked. Early in September I’d expressed my awe upon reading the unforgettable Chess Story by the same author. Zweig’s mind seemed to plumb the depths of a human being’s psychological moorings, and as I said in the post about the book, “I was disturbed and addled by the time I reached the end”.

Once again, in this novella, Zweig takes us into places that we recognize only when someone more insightful than us pulls apart the curtain and tells us to peer in. Reading his work is like looking at our inner selves through a kaleidoscope such that, with just a turn of the scope, we become almost unrecognizable to our own selves. This novella is all of eighty pages long but it encapsulates all the passion, newness, trauma and despair of a love that will not—rather, must not—achieve consummation.

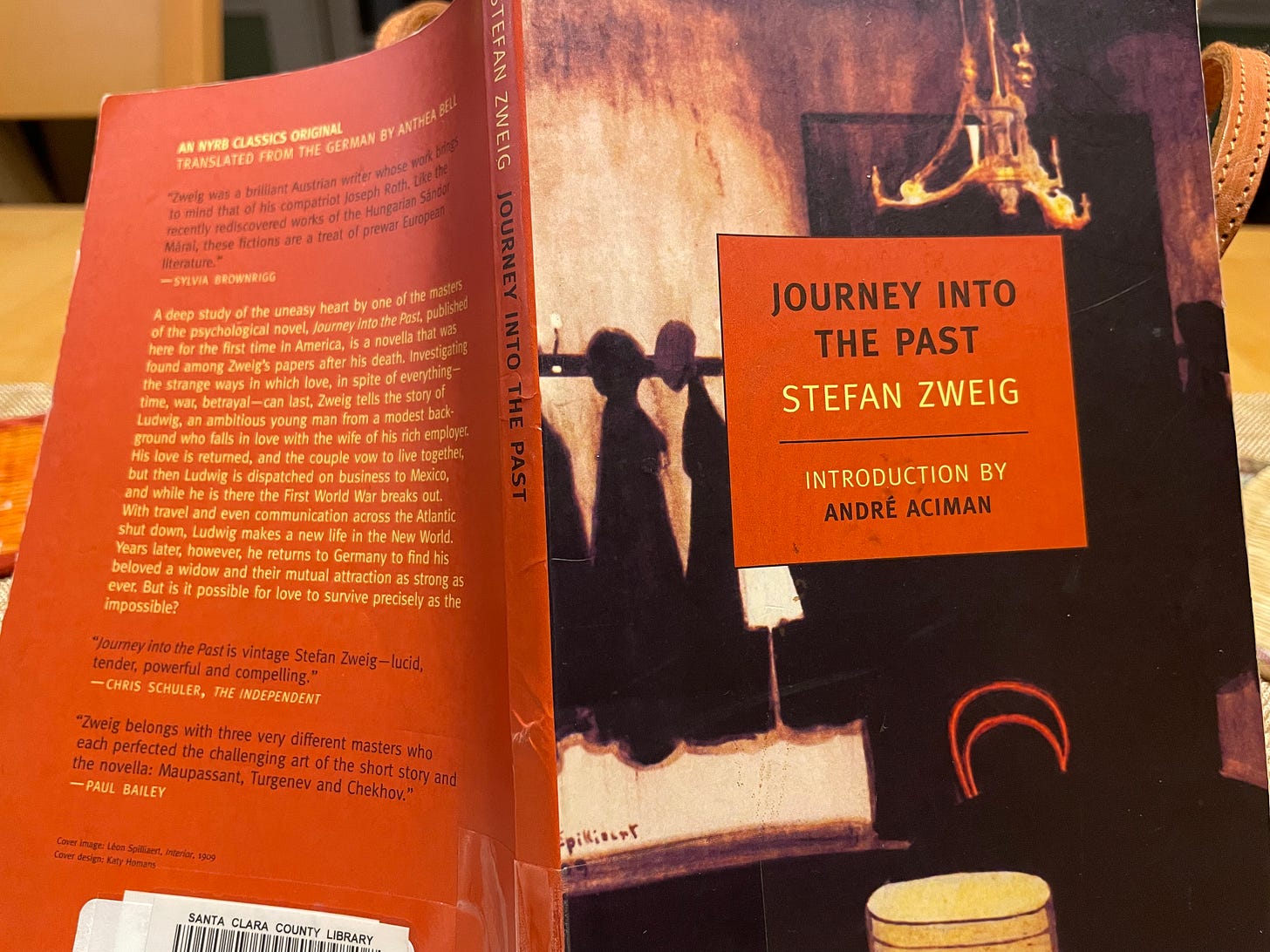

What also attracted me to the novella were two other things. I love the selections published by the New York Review of Books. Their chosen works are always classic tales, of course. They also present them alongside a thoughtful introspection on the story by a terrific essayist. The prefatory essay to Journey Into The Past is by Andre Aciman whose writing I absolutely adore and it brings the import of Zweig’s story into relief. The story is so exquisitely delineated by him that it also enhanced my reading pleasure.

Journey Into The Past was discovered many decades after Zweig’s suicide in Brazil in 1942. It was found in London, among his papers “in typescript with handwritten corrections by the author”. According to Aciman, as the story begins, it smacks of a “B-grade, black-and-white Hollywood romance from the 1930s or ‘40s”. What makes the novella so compelling, in my view, is how the tale excavates the emotions surrounding each moment—haven’t we all been there?—and how the writer presents the overarching feelings of the “then” and the “now”.

The passage of time colors the way we think about love. Zweig’s investigation of love and the ways in which an abiding passion between two people can change over a period of time is breathtaking. Zweig tells the story of Ludwig, an ambitious young man from a modest background who falls in love with the wife of his wealthy but ailing scientist (“Councillor”) even as he lives and works in the employer’s sprawling villa. His love is requited, of course, but the lovers are unable to find the time to be alone, especially because they’re surrounded by the staff and, of course, the Councillor, too.

From that first meeting he had loved this woman, but passionately as his feelings surged over him, following him even into his dreams, the crucial factor that would shake him to the core—his conscious realization that what, denying his true feelings, he still called admiration, respect and devotion was in fact love—a burning, unbounded, absolute and passionate love.

Ludwig and his lover begin writing to each other and have clandestine meetings at the end of hallways inside the home. It’s heartbreaking to see the angst as well as the pathos in the life of these star-crossed lovers. Zweig’s use of metaphors and imagery captures the sexual longing eloquently in some passages; yet it fails monumentally, it seems, in some others. Still, it’s hard to not love the originality of Zweig’s prose.

But love truly becomes love only when, no longer an embryo developing painfully in the darkness of the body, it ventures to confess itself with lips and breath. However hard it tries to remain a chrysalis, a time comes when the intricate tissue of a cocoon tears, and out it falls, dropping from the heights to the farthest depths, falling with redoubled force into the startled heart.

A few years after he begins work with his wealthy employer, Ludwig is dispatched on business to Mexico for a period of two years. Unfortunately, just as he is about to return home to Germany, World War I breaks out. The letters from his lover come to an end, especially with travel and communication across the seas shutting down. In the nine years that Ludwig is away in Mexico, he makes a life for himself in the New World, marrying the daughter of a respected local. They have two children.

At the end of those nine years, however, he returns to Germany on work. He discovers that his lover is now a widow. Upon meeting her, he knows that their mutual attraction is unchanged. Yet everything has changed in their lives.

Yet she was still the same, a little older to be sure, on the left-hand side of her head silver threads ran through her hair, which she still wore parted in the middle, that glint of silver made her mild, friendly expression a little graver and more composed than before, and he felt the thirst of endless years quenched as he drank in the voice that now spoke to him, so intimate with its soft touch of regional accent. “Oh,” she said, “how nice of you to come.”

What I found especially artful in this work is how Zweig, without ever saying it outright, implies that the act of consummation—even if it were to not alter the course of the story—would have cheapened or taken something away from what Ludwig and the woman felt for each other. The significance of this powerful work rests in not knowing what could have been .

I appreciated another salient point made by this story, that the onus of moral rectitude invariably rests on the woman for she has much more to lose than a man, and that the peace of family life depends heavily on these moments of clarity and foresight. As the narrative rolls to the end, it’s impossible to not feel that something special and beautiful between the two lovers now remains forever sanctified.

No one came towards them, only their own shadows went ahead in silence. And whenever a lamp by the roadside cast its light on them at an angle, the shadows ahead merged as if embracing, stretching, longing for one another, two bodies in one form, parting again only to embrace once more, while they themselves walked on, tired and apart from each other.

We never get to know the name of the woman either. It seems it was a deliberate choice on the part of the author. By not naming her, she may be erased, even faster, from the minds of everyone who knew her—except, of course, from Ludwig’s own.