A MANUAL ABOUT THE SELF

The late José Saramago, the 1998 Nobel Laureate, is a household name in Portugal and in the world today. There was a time few knew about him and that's why I sought to read his very first novel.

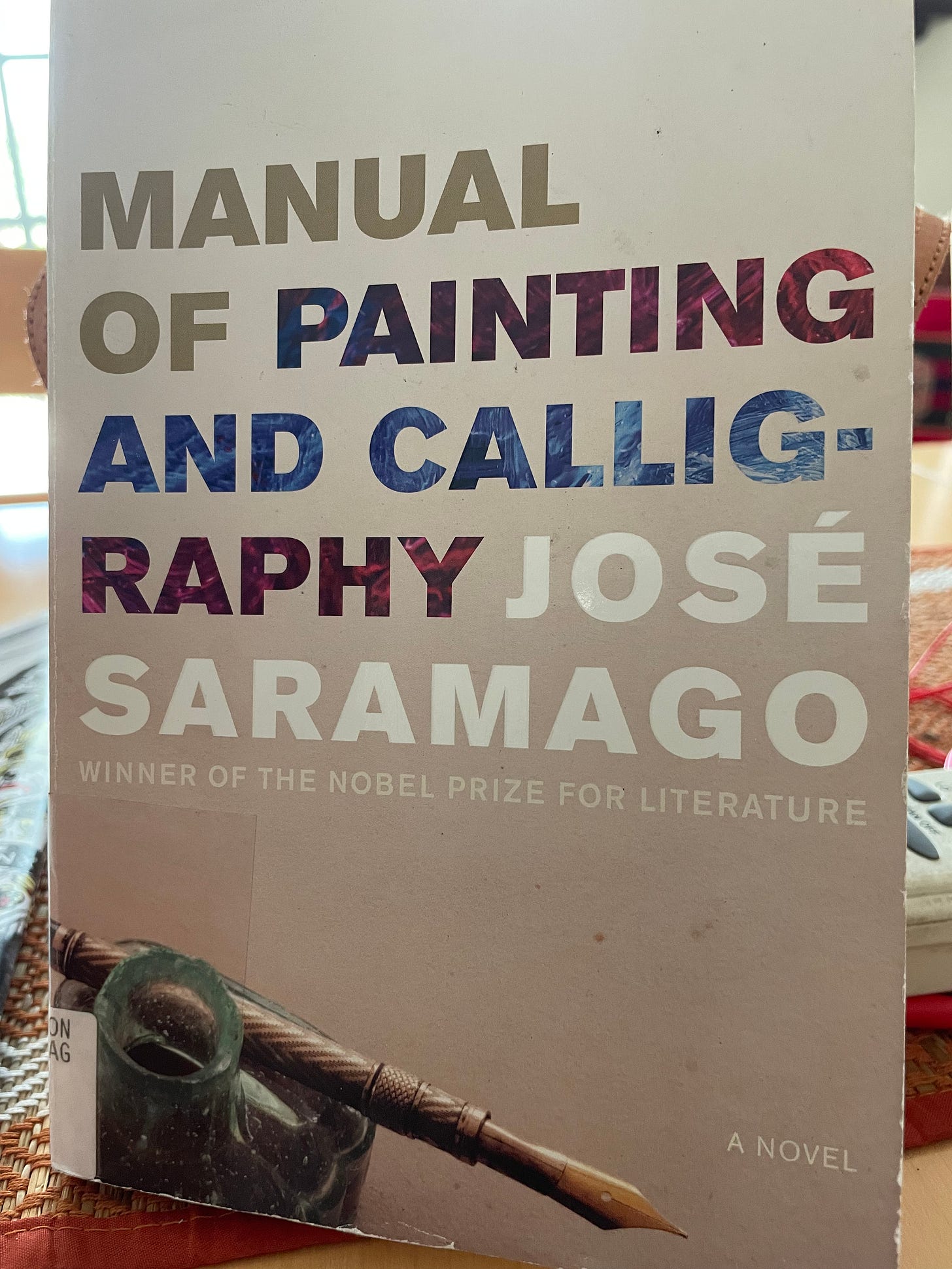

Manual of Painting and Calligraphy is the first novel by Nobel Prize-winning author José Saramago. He certainly writes with verve and style, much like Garcia Marquez and Javier Marias, dipping into long, loopy sentences that are are as lyrical as they’re funny.

While I stayed with the novel (as much as I could) and certainly enjoyed several passages of his writing, I’m afraid I had a rough reading experience this week. José Saramago’s novel is slower than molasses. As the story progresses, we realize that this is a story of self-discovery as well as an exposition of the world around a painter set against the landscape of a dictatorship.

Manual of Painting and Calligraphy was first published in 1977 and an English translation by Giovanni Pontiero of this Portuguese work was published in 1993. The plot of the novel involves H., a painter who paints elite and arrogant people who are vain enough to want a personal portrait in a world that has just discovered the possibilities in photography.

We learn that our narrator, the painter, has been critiqued negatively by the people whose opinions matter in that world. As the novel opens we realize that he seeks to not be in the public eye because of the world’s specific view of him. He has not just been ostracized. He has been forgotten. All he does is paint portraits now for a fee that he demands be given in cash. There is no lack of work, as he admits, and he guarantees durability even if he does not guarantee art. He clearly lives on in acceptance of this mediocrity although, quite clearly, he is not satisfied with himself.

None of this gives me any satisfaction, because I am merely observing the rules, protected by the indifference which critics have used like a cordon sanitaire to isolate me; protected, too, by the oblivion into which I have gradually fallen, and because I know that this picture will never be exhibited in any gallery.

This is an exploratory novel, it seems, both for the narrator in the novel and for the author himself. For the first 75 pages, I found the narrator unpleasant and toxic. He is like the arrogant friend who wants to show off that he can wax eloquent about the world of art but then when he returns to the subject of his own pursuit of art, he won’t stop the self-deprecation. He knows what he must do and seems to have the knowhow, but he just won’t persevere seriously enough at his art. Instead, he prevaricates and overthinks everything he does. In one instance, the narrator in this novel goes to extraordinary lengths to destroy a second copy of a painting that has been commissioned for a high sum. What’s shocking throughout is how he has so little confidence in his own brush; instead, all he does is see himself through the eyes of the lay public. He’s quite the existential wuss.

The paint is dry, the portrait is good, technically speaking, and guaranteed to last. In these matters, I am the best painter in town. But in this city I am also the greatest failure alive. I have never successfully completed any of my projects and not even these sheets of paper have increased in volume since I started writing from scratch. It is over and done with. I tried, I failed, and there will be no further opportunities.

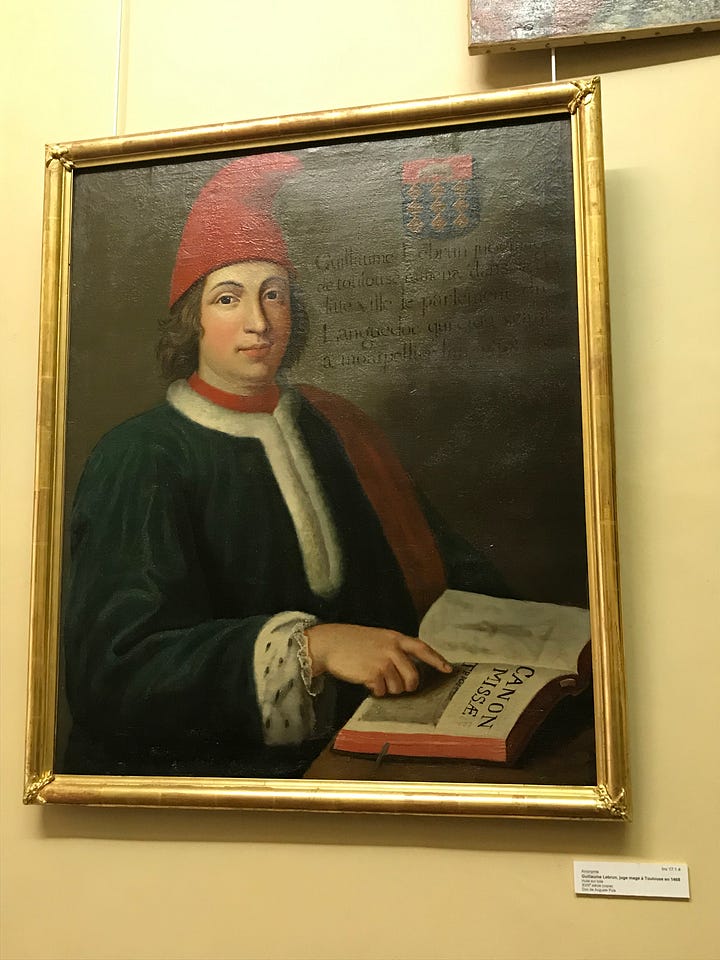

The novel dives into several discussions of paintings and how to think about the medium, and even in its most ho-hum segments, what kept me interested and reading were the many references to painters and their masterpieces. We walk into sacrosanct spaces where the world’s great masterpieces rest.

Then there is the Church of Santa Maria delle Grazie. Alongside, at the spot where the refectory of the Dominican convent stood, is Leonardo’s painting of The Last Supper, already doomed to perish as the painter applied the final brush-stroke, for the dampness of the site had already begun its work of corrosion. Today, dampness has transformed the figures of Christ and the apostles into wan shadows, has covered them in mist, pitting the picture all over where the paint has peeled, a constellation of dead stars within a luminous space.

Manual of Painting and Calligraphy is a treasure trove for painters, art historians and for anyone who wishes to experience art in Italy; Saramago escorts us into Milan, Arezzo, Rome, Florence and Perugia. While reading some of the passages, I wondered what my friend Claire Ossola, who writes the terrific

would think of this novel.It’s not an easy read for several reasons. It’s harder to keep reading a book when you don’t feel particularly empathetic towards the narrator. With the exception of some hopping between the pages in the mucilaginous bits of the tale, I kept reading to see what exactly the narrator was seeking.

Through the narrator, we learn that there are differences between painting and writing. There are some similarities, however; we learn that a painting reveals as much about the painter as it does about the model being painted. We find that as time goes on, the painter-narrator’s writing becomes clearer. As his sense of purpose sharpens, it is reflected in his pen, too.

I began to see that that painter’s growing self-confidence helped him take charge of his reactions to how his clients responded to his work. In a memorably cathartic scene, the artist returns home from his client’s home with his work in his hands, “reclaiming” his sense of self.

Manual of Painting and Calligraphy is downright hilarious sometimes in the use of language, the sharing of a fact or an observation made about the world. In a brilliant moment early on, the narrator weighs in on the terror of the revolving door in a public building. It completely resonated with me and had me in splits because I’m always worried that the revolving door through which I just passed will whack me on my back if I don’t hurry through it. Since this novel was written in 1977, I can imagine how much more terrifying these things may have been then.

SPQR also has one of those revolving doors which I regard as the bourgeois version of that boulder covering the entrance to the Cave of the Forty Thieves. It is not called sesame (a plant yielding gingili oil), and it represents the supreme contradiction of a door that is simultaneously always open and always closed. It is the giant’s glottis, swallowing and spitting out, ingesting and vomiting. One enters in fear and emerges with relief.

The motif of the revolving door becomes important. As the narrator expresses his angst with regard to his profession, he begins to tell us how he must write about his painting and his life in order to discover more about himself. While he sets about writing about his life, we take a peek at his love life, his infidelity and his disenchantment with the ways he uses the very women who use him. Quite naturally, love and sex are one of H’s preoccupations; I felt that some of Saramago’s most spectacular bits of writing were in the erotic scenes.

The artist steps out of his world of painting in order to write but we also watch him returning to his world of art through that metaphorical revolving door after he has roamed about in the world of writing and received the clarity to pursue his art. In his search for this acuity that seems elusive to him, we too learn a few things about how painting, sculpture and writing were known by the same term in the medieval era. They were referred to as “writing”—for they were considered an exploration of sorts by the mind, a fact that is lost to us in these times.

Thanks for putting this novel on my radar! I’ve only read his “Blindness,” which was simultaneously difficult and enthralling. His lyrical writing paired with the subject matter of art—well, sign me up! Fantastic review!

I think I'd enjoy this novel, the excerpts you posted – especially the 'Last Supper' one – are really good. Thanks, Kalpana, for your intriguing review.