A BULLET OF A NOVELLA

This Natalia Ginzburg's novella is the quintessential novel about heartbreak and agency.

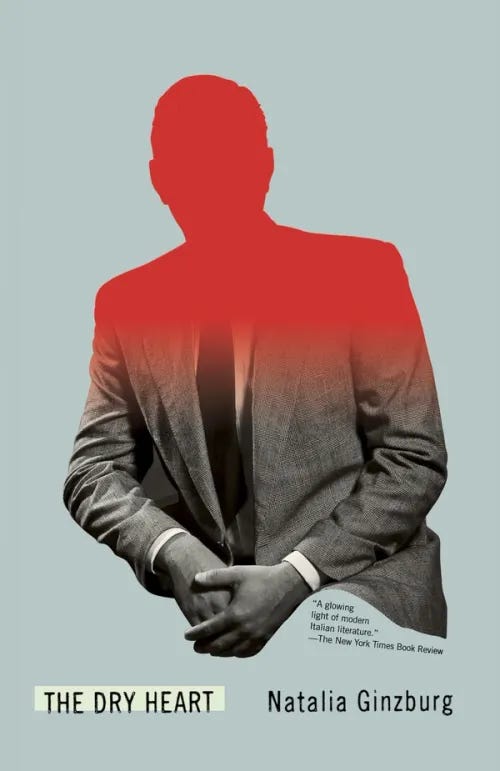

At 88 pages, Natalia Ginzburg’s The Dry Heart (translated from the Italian by Frances Frenaye) is one of the quickest reads ever, and a perfect choice for a travel day across the country. The novella’s potency begins with the opener below and the tension doesn’t slacken once in between.

“Tell me the truth,” I said.

“What truth?” he echoed. He was making a rapid sketch in his notebook and now he showed me what it was: a long, long train with a big cloud of black smoke swirling over it and himself leaning out of a window to wave a handkerchief.

I shot him between the eyes.

This last line is a refrain that returns to us several times in the book after the opener. We read it at the end, too, when we have a much clearer understanding of the marriage and the state of the two people caught in it. It’s an absolute missile of a sentence from a woman who finally assumes agency of her life and decides she just won’t settle anymore.

When I was writing my first book, a writing mentor who read my first chapter told me that I needed to establish that my father had died right in the opening paragraph of the book. “Once you establish that, people won’t want to quit reading until they know how exactly your father died,” she said. I found that advice to be invaluable as I was building my book. Almost all of us have an undying curiosity about the circumstances that leads to someone’s last exhale. That’s what gives this The Dry Heart its heft right at the outset.

That being said, Natalia Ginzburg takes us to another level in this psychological thriller by peeling the layers of a marriage which, by some cultural estimates, may even be considered a decent enough partnership. By the time Alberto and the nameless woman—a school teacher—run into each other for the first time, he is 40 and she is 26. Notwithstanding the difference in their ages, the teacher realizes she has fallen in love with the man.

Then it was that I came out with the whole thing. I told him how I tormented myself waiting for him at the boardinghouse, how I couldn’t concentrate on correcting my school papers, how I was gradually turning into a complete idiot, all because I loved him. I turned to look at him after I had spoken, and on his face there was a sad and frightened expression, which I knew meant he didn’t love me at all.

Now here is the tragedy of this story. We preside over the marriage of two people knowing fully well that the man’s heart is not committed entirely to the marriage. We discover that he may even have married the school teacher out of spite; he was angry at his lover and knew that if he could not have her her could at least hurt her by marrying someone else. We know also that he proposes marriage to the woman when his mother dies, in a moment clouded with the sorrow of his enormous loss. He’s a sniveling cad who, thank god, shows himself to be rather caring during some very dark moments in his wife’s life.

Without giving away the entirety of this story, what Ginzburg shows us in brilliant strokes is the slow psychological rupture of a woman. By the time the story closes, every reader knows why she must pull the trigger.

We discoer that the unnamed protagonist in this story is a clear choice by the author. She represents all those women who endure, especially those trapped in a loveless marriage with a man who is selfish, manipulative and indifferent. What makes this story heartbreaking is what does the woman in after the couple decides to separate.

I got undressed and looked in the mirror at my naked body, which now belonged to no man. I was free to do as I wanted. I could go for a trip with Francesca and the baby, for instance. I could make love with any man who happened to catch my fancy. I could read books and see new places and discover how other people lived. In fact, I ought to do all of these things. I had made a mess of my life, but there was still time to set it straight. If I made enough of an effort I could turn into quite a different woman.

At this crucial moment in her life, when she’s about to take charge of her trajectory once and for all, something happens to alter the course of both their lives. We can plan all we want but what does destiny have in store for us? The Dry Heart is desperately sad and captures the fragility of our existence with such depth and precision.

For me, the novella is much more than a feminist plea. It’s about embracing action over inaction. The lethargy and inertia demonstrated by the central characters in the story costs dearly. That’s why, in my view, our narrator’s decision to shoot her husband between the eyes, is the most transcendent moment of all. She is clear. She has come into her own. She deserves to be free.

Wait. Shouldn’t they go to marriage counseling before trigger therapy?