A BIT OF AN IMPOSITION

The first of a triptych, this French book was a little too disconnected and highbrow for me.

Once in a while I come across a book in which the blurbs confound me. A few pages into Nathalie Léger’s Exposition—translation from the French by Amanda DeMarco—I was puzzled by what Publisher’s Weekly found “remarkable and engrossing” in the story. Here was one of the strangest works of “fiction” that, for the most part, seemed to be non-fiction.

When I finish reading a work, it seems I should be capable of stating its import in a succinct line. Exposition doesn’t lend itself to that. On some days it felt like an imposition. Still, I stayed with it. If anything, this experience of reading weekly—and writing weekly—has taught me to persist and try to make sense of a work during the time I’ve given myself.

Exposition is the first of a triptych—a set of three associated artistic works to be appreciated together—where Léger explores this notion of someone’s artistic journey in the world. Is the artist creating art or is the art creating the artist?

This is a question Léger asks early on in her novel. It’s worth contemplating in any endeavor. It’s the rare writer who makes us stop and ponder something; Léger’s mastery of her craft made me want to reread her sentences in some instances. Yet, for me, the work lacked cohesion and I’m left wondering if Exposition cannot be experienced on its own, without finishing the other two in the triptych.

The narrator in Léger’s work is fascinated by the preoccupations of a woman in the mid-nineteenth century. While following Léger’s thoughts, we get to experience her analysis of an artist and note the workings of her mind. Léger probes the life of a woman who was believed to be the most beautiful woman in a century. An Austrian princess professed to have been awed upon seeing the woman.

“I was petrified before this miracle of beauty: marvelous hair, the waist of a nymph, complexion of pink marble! Like Venus descended from Mount Olympus! Never have I seen such a beauty, and never shall I see another like it!”

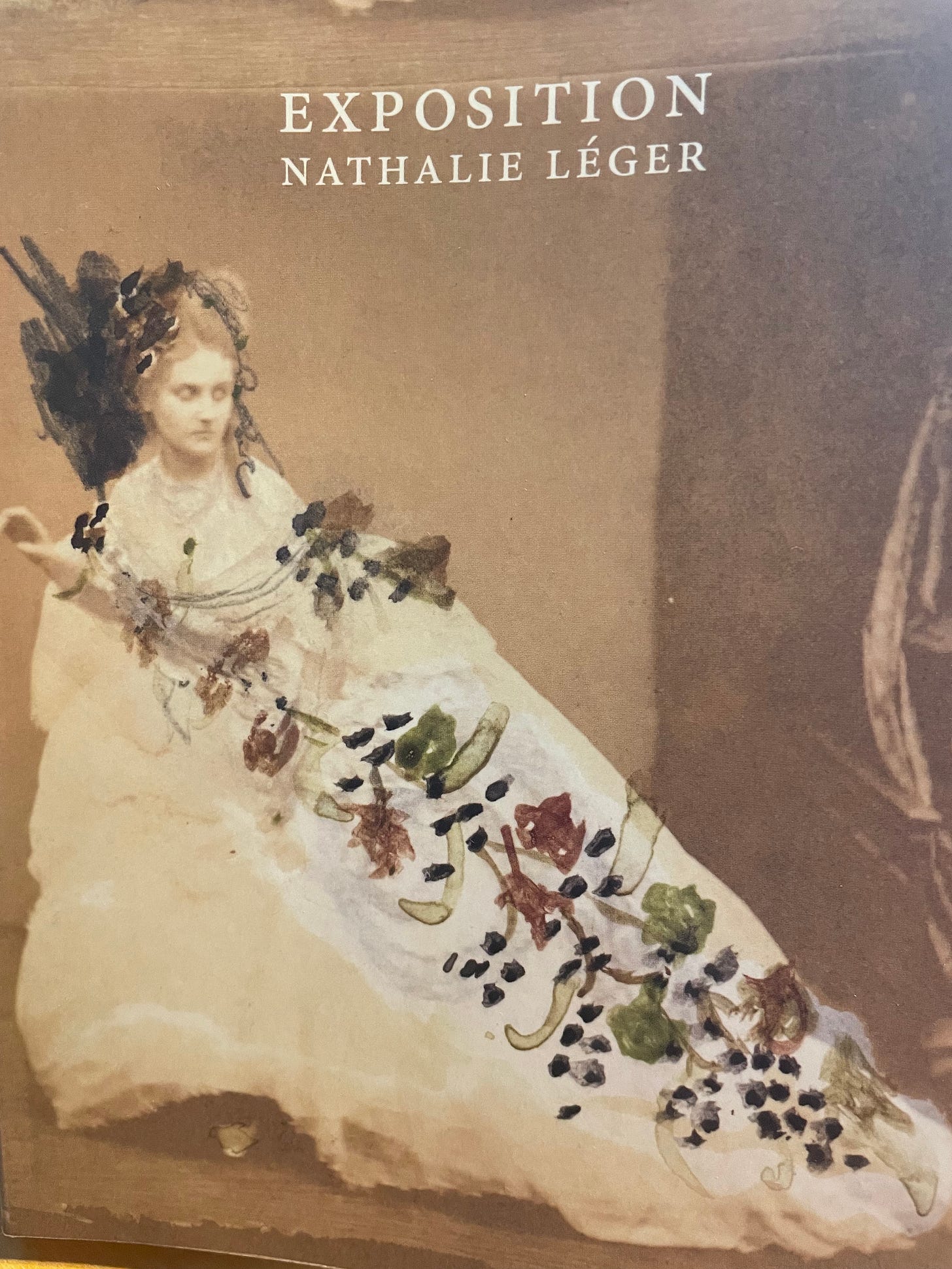

The beauty was Virginia Oldoïni, Countess of Castiglione (22 March 1837 – 28 November 1899), better known as La Castiglione, an Italian aristocrat who became Napoleon III's mistress. The affair between the emperor and his Italian mistress caused a scandal in Paris and led her husband to demand a separation. What kept her in the gossip columns of Europe’s salons was something else that the countess sought during the course of her life all the way until her death.

In an era when women were supposed to aspire to the heights of modesty, La Castiglione sought to ruffle feathers (while often preening in them) even as she became a recluse. She craved to be photographed. She might have been the selfie queen of this generation for she often told her photographer, a man who recorded her life over a forty-year period, how to choreograph each moment during which she was the subject.

The photographer, Pierre-Louis Pierson, captured all of France’s most illustrious society people of the period on his camera and was also the emperor’s official photographer from the year 1853. One July day in 1856, the young Countess of Castiglione appeared for the first time at Mayer & Pierson, the photographic studio for high society. She knew what she wanted and made it clear. “She has no need for him to be an artist, nor to do any soul-searching. She only needs his expertise and his discretion.”

Leger notes that Pierson “let things happen, that he would direct from afar and with few words. As for the rest, the scene, the intention—in short, the art—it’s no use, there is nothing to be done, she takes charge of everything.”

I felt that Léger’s motive, especially from the perspective of an archivist, was to also take us on a journey into the mind of a woman in control of her story—through the exhibits she had left behind for posterity, some 700 photographs from the different moments of her life, some of which even included pictures of her feet and of a breast. Leger tells us that La Castiglione was both beautiful and unpredictable—in front of the camera and in real life.

She appeared nude for a happy few, men who came in the evening to hold their salon around the recluse. If boredom won out, if conversation lulled, she revealed the ace in her sleeve: nude, she appeared nude.

What I found breathtaking in the life of the countess was her self-confidence in what was predominantly a man’s world. Why did she want to record the small and big moments of her life? Let’s consider how she manipulates her audience in an incident following an international trade fair in the city.

The city of Paris held the Universal Exposition in 1855. It was a highly successful international exhibition during which a famous portrait of the countess (as the Queen of Hearts) was exhibited. Several years later, in 1863, La Castiglione was invited to participate in a charity event. The organizers were hoping to sell tickets in the hope that La Castiglione would shock them. When people knew that she would be attending, the tickets sold out. What La Castiglione did at the event was one of my personal highlights from Nathalie Léger’s work.

The charity party took place at Hotel Meyendorff on Rue Barbet-de-Jouy. They hoped she would be nude. The rumor had gone around that she had demanded a grotto setting, and they imagined her unclothed as a nymph, a siren, as Ingres’s Source, against a canvas backdrop painted like a cake. A packed house. When the curtain rises, to their astonishment, it is a nun who appears at the doorstep of her hermitage, dressed in the attire of a Carmelite, made of severe homespun, the hostile face obscured at the forehead and chin by her veil, her posture stiff. A little sign on the cardboard reads: “The Hermit of Passy”. Silence.

While reading a little about the subject of Léger’s second book on actress Barbara Loden, I got a little more clarity on what she was trying to do with Exposition. Loden’s observation below summarizes the relationship between art and its creator.

"I don't see how anybody can predetermine how their movie is going to turn out, or why anybody would want to, because it's a creative thing that is changing every day, and you're changing every day while you work on it. You start to make a movie, and when you finish it you'll be a different person."

–Loden speaking at the American Film Institute, 1971

The background to Loden’s directorial debut Wanda—a 1970 American independent drama film written by Loden herself—gave me clues. Loden stars in the title role set in the anthracite coal region of eastern Pennsylvania and plays the role of an apathetic woman on the run. Much of the dialog and filming was improvised, with Loden only loosely referring to the screenplay. Reading about Loden helped me piece together what Leger recognized in La Castiglione.

Some women may seem rudderless. Yet they are indeed at the helm. Like Loden, La Castiglione actually manipulates the camera and our gaze. When La Castiglione sat for her first photograph she knew she was on to something; she knew that her intent, especially in a man’s world, was to be seen and heard for many decades. I believe that as time went on, even as she became less desirable, La Castiglione began recording the ephemeral nature of beauty and the long, painful decay of all living things, the putrefaction and, subsequently, death.

Exposition opens with the following lines. Later, long after I turned over the last page of the book, I realized that the words were written for all those who, for a few tenuous moments, get behind the camera to shoot and capture a moment for posterity. It’s about just being present and clicking, without judgement, for in the end this too shall pass.

Surrender, premeditate nothing, want nothing, neither discern nor dissect nor state, but rather shift, dodge, lose focus and—slowing down—consider the only material that presents itself, as it presents itself, in its disorder and even in its order.

It sounds like La Castiglione considered herself a performance-art piece, and was a century ahead of her time at that. Fascinating to consider the implications of that, given who her art patrons were (Napoleon, a bunch dudes at a boring party, awaiting her nakedness). Was she exploited, or the exploiter? I guess I’d have to read the book to decide.